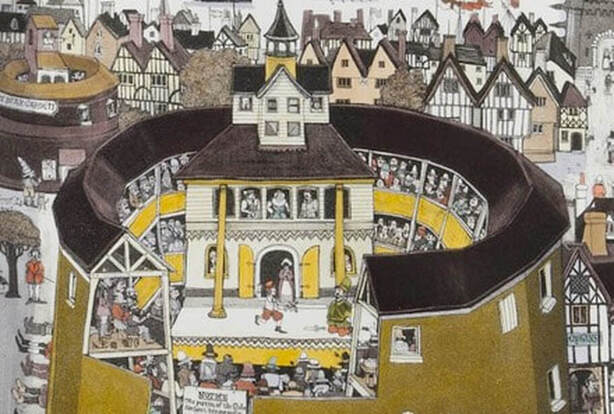

"You may have people in your life who don't expect much from you — don't value your potential or input — for whatever reason: too young, too old, too inexperienced? I am not one of those people." If you’re an actor who’s been in one of my theatre productions, you've heard me say something like the above... on the very first day. And as rehearsals progress, you've probably also heard my favorite mantra: "That was perfect! Now do it again." When I direct, I tend to treat young actors like they’re adults and all actors like they're professionals - each one of them with opinions and ideas that matter. And if all goes well, by the end of a production the actors own the show as much as I will... because that's when the magic happens.  These are some of the best actors I've ever had the pleasure to work with, each an expert in character development. L to R: Sue Derrow, Maddy Curtis Vencil, Garrett Milich, Christopher Saunders and Suzy Alden rehearsing a production of Oscar Wilde's IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST. Photo by Craig Thoburn. I learned how to direct while running a non-profit theatre company for 10 years and producing 30-some shows. Some directors held BA's in theatre, some held Masters and others worked by the seat of their pants. And I? I received my education watching all of them. Some wanted actors to do exactly what they told them to do... which is fine if a director is brilliant and creative and can get actors to actually DO exactly what they say (But if the director is not, well...). Others expected actors to memorize lines at home and spend most of their rehearsals doing "acting exercises". And if the actors were able to fight the boredom, they''d make it to Opening Night. Some directors use a style professional directors use: they think all their work is done in casting and expect the actors to show up with their lines memorized - ready to go! But this only works in professional theatre. And then there were the three directors I studied intensely - the best of the best: Dolly Stevens, Tim Jon and Tom Sweitzer. All three would begin with respect for the actor and end with actor ownership of their role/s, and I cannot direct any other way. After 10 years of learning, it was time for me to direct. I took the company I'd used to produce history documentaries and public programs for museums and started producing and directing local theatre. BUILDING A PLAY ONE CHARACTER AT A TIME So, about those professional actors who just show up ready? Yes. I want actors to internalize the process like professional actors do - with things they would have learned in drama school. So I'll start them off with the my Director's character concept, but then ask them to read the script and make that character their own. I encourage full character development, even if they have no lines or are a member of the Chorus. And I like some exercises done at home, because they desperately need time to build the scenes on their own... then together. The main reason I like doing acting exercises in rehearsal is simply to let the actors get to know each other and respond to their various characterizations. As we go along, I'll teach Method Acting, which involves improvisation and emotional recall, and then go over how they might best learn a script: audio, visual or movement - whatever helps them get where they need to be. And as rehearsals progress, I'll start soliciting their ideas. And if their idea serves to: 1. Further the plot, 2. Reveal more about their character, or 3. Set the audience up for a pay off (in this scene or a later one), then I’m going to try to work it in. When actors of any age approach a play this way, they start finding relationships and possibilities that as director I might have missed. And I will always want to be open to their idea, because amazing things might come of it. BE WILLING TO KILL YOUR FABULOUS IDEAS When I became a published author years ago, I had to defend my choices to an editor - based on the same three rules above. So what if I spent five hours crafting that paragraph, or thought I had the most clever conversation going? If it doesn’t develop a character or relationship, further the plot, or provide a payoff, I had to be willing to let it die. Note: clearly this requires the director to know the play inside and out, because if you haven't prepared yourself, you're going to get defensive. Add a really tiny ego, and you just... might... SNAP. So in my directing world, I have to come in prepared and confident... but also realize I might not have the best ideas in the room. Yes, I know I have a creative brain, but why wouldn’t I tap into a larger creative brain if I had the chance? Actors have more time to dive into these characters. Give them the space, and they're going to find things there I didn't see. And as all the actors do the same, relationships and situations things are going to happen - good things: "If she's going to react that way because of what happened earlier, as her sister I would know that, and that completely changes the way I should react..." Above: the stellar cast of Run Rabbit Run Theatre's TAMING OF THE SHREW And, as a result of all of the above, actors begin to take ownership - of their characters, a scene and the play itself. And this is where the magic begins. So even though this will replace the absolutely brilliant idea I had as the Director, well... gulp... let's do this instead. And the audience will thank you for it... literally. BUT WHAT ABOUT THE REALLY BAD IDEAS? Okay. What if your actor comes up with an idea that just won’t work? Is truly horrible? Makes no sense to the character's history, etc.? And they present it to everyone before I've heard it? Then I have to thank them for the idea, say No, and tell them why. Why? Because 1. I want them to know suggestions are respected and appreciated, and the next one they have may be perfect (and often are), 2. Explaining why it won't work helps everyone understand more about the character, the plot or the scene mentioned, and 3. An explanation gives everyone in the cast a chance to further understand the setting, the character or the plot of the whole thing. Obviously at this point a couple of things are crucial: a directors needs to love their actors enough to know how to say no diplomatically or actors won't offer ideas for fear of retribution. But directors also need to avoid wanting actors to loooove them, or they'll never know how to say no to a bad idea, and the whole cast and the whole play will suffer. But, in the end, whether a good idea or a bad one, thanks are due to actors. Because their process and commitment is how a good play becomes great. ACTORS' INSIGHTS WITH PHIL ERICKSON AND PENNY HAUFFE - 4-minute Video (Click!) LAY DOWN THE GROUND RULES Lest you think rehearsals should devolve into a free-for-all “sharing time,” I'll point out ideas are solicited only at certain times in the process: 1. Creative input falls mostly in the beginning of the rehearsal schedule. Group discussion is good. And this is also a great time for the Director to underscore the story arc of the play, the scenes, and the characters. 2. Then when we begin to run scenes regularly, actors are asked to hold their ideas until the next break - and then share those ideas only with the director. 3. Crucial to the entire process: actors do not get to suggest what other actors can do. Ever. They can certainly ask why another character does something, but... that's it. Simple reason: every actor must be entirely focused on their own character/s, their actions, feelings, backgrounds, etc.. This is the process professional actors use, and I love bringing it to community theatre, because, when actors take this process on, shows get reviews worthy of professional productions (Think I'm lying? Check out Run Rabbit Run Theatre reviews). And when an actor is completely focused on developing their character in a scene, it often leads another actor to have a revelation about their own character. Lastly - without exception - an actor should never simply tell another actor to “do it this way" or "try it this way". Why? Well, because that would be called directing.

0 Comments

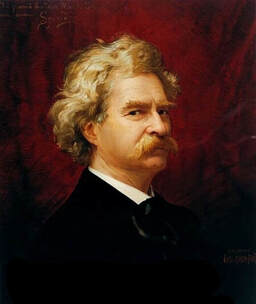

MARK TWAIN MARK TWAIN "Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one's lifetime." - Mark Twain I was reading a column about Mark Twain's book, Seven Life Changing Lessons You Can Learn from Mark Twain (“Dumb Little Man" Column, Business Insider), and I thought, Hey, this MY life, for pity’s sake! My weird little theatre life, with its broad, odd, wholesome, creative, charitable views of the world - found all because I chose NOT to vegetate in a little corner of life. And those that join me in organized chaos have the pleasure of inhabiting dozens of people and perspectives, new worlds and old, and all sorts for magic and mayhem. "I have been through some terrible things in my life, some of which actually happened." - Mark Twain Well put, sir. For the pleasure of inhabiting a completely different perspective for a time, an actor will risk self-respect and criticism, face sleep deprivation and midnight terrors. and live through some terrible things. And the things that happen to them in real life? Those feed into the actor’s art and enhance the richness of every character portrayed. "Don’t go around saying the world owes you a living; the world owes you nothing; it was here first." - Mark Twain Ah. The actor who walks into auditions wanting a particular role… then argues with the director about casting choices. Yes. That’s going to go over well; do that. And then try auditioning again… anywhere but here. Of course, Twain could also be describing life as a director. And, yes, I tell myself to get over myself... a lot, actually. And I better, because… "When people do not respect us we are sharply offended; yet in his private heart no man much respects himself." - Mark Twain I hate a bad review, but if I don’t leave room for improvement, what do I think I am, perfect? Ridiculous notion. Every really good actor I know doubts themselves, because they’re always reaching for perfection. Conversely when an actor has said (however shyly) they believe they are good, nothing good has ever come of it. And then there is Twain's great advice for getting organized: "The secret of getting ahead is getting started. The secret of getting started is breaking your complex overwhelming tasks into small manageable tasks, and then starting on the first one." - Mark Twain Spot on, spot on. And when chaos descends — as it will, without fail, one to ten days before opening night - I remember these wise words, as well: "When angry, count to four. When very angry, swear." - Mark Twain Twain may not have been thinking specifically of the theatre when writing this last piece of advice, but it sure does come in handy to a thespian - it certainly does. 1) If the Very Important Teacher From Britain Who's Worked With the Globe Theatre ever asks you to share any facts you might know about Shakespeare, say something no more detailed or thoughtful than, "Uh... born in England?" or you will be asked why you bothered to come if you already know everything.

2) The teacher is likely to tell you it is ACTing, not thinking... blinking... snorkeling... especially not thinking. 3) While noting Shakespearean scansion, the five beats of a line should be counted on five fingers: pinky first, thumb last, last, last, while saying "te-tum" on every beat. No, I said "te-tum". Now say it again... You still haven't got it. 4) Teacher may ask you to perform emotional recall even while claiming this is NOT Method Acting, forgodssake (similar to any politician promising four years of things like peace and prosperity). 5) Consider the possibility that Stanislavsky frightens the English and is a good subject to avoid. 6) Read Shakespeare aloud with your tongue stuck on your lower lip, because - you must assume - Teacher thinks public humiliation is good for you and this classroom exercise will - at the very least - perk up Teacher no end. 7) Also consider the possibility that Teacher's solid need to humiliate each and every student has nothing to do with the educational process and everything to do with a little voice inside Teacher's head that says, "That'll show mother!”. 8) Teacher may also hear a tightening in your throat which is completely imperceptible to you. This will indicate to teacher that you are a SELFISH actor who never gives ANYthing to an audience. When this happens, the proper thing to do is stop breathing and smile, because if your throat wasn't tight before, it is bygod tight now. 9) ... and note-taking. Stop taking notes. 10) Did I hear you thinking? I didn't tell anyone what I did - not even my partner in life. Just quietly filled out the application and took it to a mailbox. Stomach queasy, I shut my eyes and took a deep breath. Ka-thunk. Why did I keep it to myself? Because if you're an author and a playwright, 9 times out 10— Make that 999 times out of a thousand - you're going to send your sweet little puppy off and never see it again... or you'll get a letter back telling you how ugly your puppy is. So I was more than surprised to receive notification that my play, Case 22, made it into the 2010 Capital Fringe Festival in Washington, D.C. And in 2010, there had been an 80% increase in applications and a long waiting list, so it felt pretty good to make it. Made me feel as though I'd won something, and I guess I did: I won an opportunity to produce a play that is, as Shakespeare would say, "not for all markets." Certainly not for my local market. Case 22 is a dark farce — not the sort of fodder folks people are used to seeing around here... or seeing me produce… or seeing anyone produce, actually. So why did I write a dark comedy? Well, Playwright Martin Blank’s has said great playwrights, “ask important questions and then try to answer them”. No, I don't pretend to have the answers, but I do believe Case 22 asks an important question like this: When a sane teenager wants to leave an abusive home, why does they have to be deemed crazy before they can get any real protection? Somebody will argue (and many have) that social services is there to help those teens, so we there's no need to be concerned. Well, those people are welcome to write a play about all the happy endings out there, but they’ll have a hard time finding them. Case 22 is based on true events and represents the statistical majority. In the world of social assistance, there are 2 incontrovertible facts : 1) Physical abusers rarely stop abusing, and 2) American courts are generally geared to keep families together "at all costs." So happy endings are rare as hen's teeth. So where did I come in? Well, I’ve worked in local theatre for many years, and that world is filled with open, accepting, kind, generous, and enthusiastic people. Due to this unconditionally welcoming environment, unusual kids find safe haven here... including the children and young adults who live in abusive homes. And Case 22 came to me while I was producing a play and getting to know yet another young teenager who'd found a degree of refuge in theatre. She couldn’t contact Social Services for fear of retribution, but we asked if we could do it for her. She agreed, and in no time at all, we smacked up against the two facts above: "The abuser will never stop abusing", and “We have to keep that family together!” As a result, despite our best effort to engage the system in her protection, she got little help. Soon after this, Case 22 came to me in a torrent - words pouring out of me as characters screamed their stories in my ear. I waited for a production opportunity to present itself, and when the Fringe application deadline loomed, against all odds I went for it.

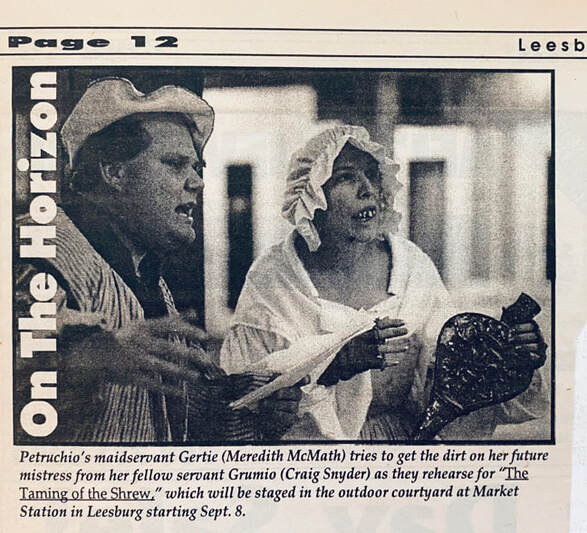

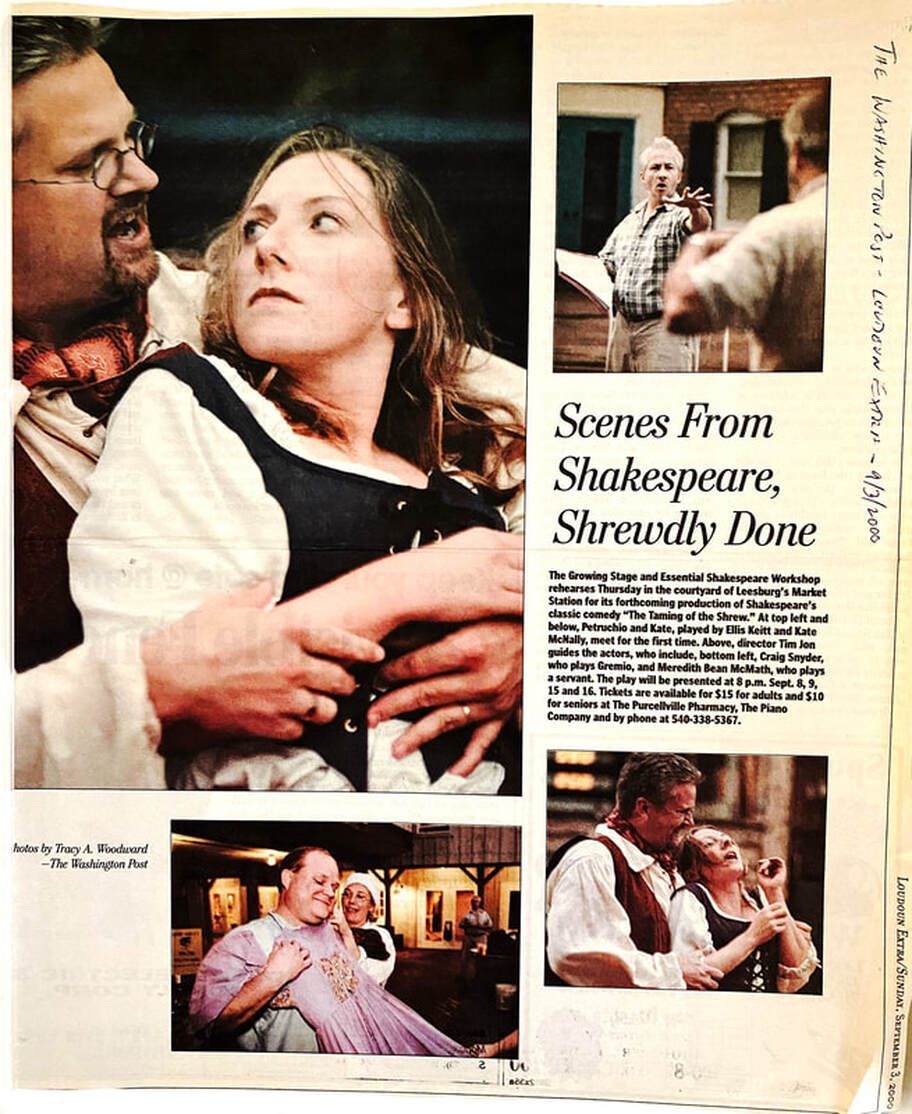

Naturally when it was accepted I became terrified — terrified it wouldn't come together as hoped, that no one would come, they'd come and not understand, or get a bad review and I'd have to deal with it — who knows what. But I was wrong on all counts, with a grand finale of an excellent review from DC Metro Theatre Arts. So, while the most worthwhile questions are the most frightening to pursue. They are definitely the most worthy to pursue. And I have a host of important questions to ask. Don't you? Ka-thunk.  Actress Danica Riesberg as Bianca in THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Actress Danica Riesberg as Bianca in THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Yes, live theatre is the place where miracles can happen. And, for that possibility - the joy and pleasure of bringing a play to life and bringing an audience to their feet - the risk of public humiliation is always worth it. But the risk is real. Forget a line and had to improvise? Missed a cue and forced the entire cast to improvise? Your skirt fell down!?! I've seen it all. But I’ve also seen a struggling actor “click” with the character on opening night and bring down the house. Worth it. So what do we do about those nerves? For me, they show up in nightmares - the one where your history professor is performing your wedding ceremony and you realize you're dressed in pajamas. Nightmares involving public humiliation are the worst, and that's why I consider actors the bravest of the brave. When the army is forming a front line to charge the enemy on the battlefield, bring up the actors. Just tell them that beyond that row of critics holding semi-automatics there’s an eager audience waiting, and off they’ll go. And in community theatre, they don’t even get paid to run that gauntlet. Many, many years ago, I became a volunteer in the acting army when I joined the cast of the former Growing Stage's production of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. I hadn’t been in a stage play since college where I was cast as Angel #2 in Medieval Plays for Christmas at William and Mary. I had one line. What I learned from that experience? When the moment arrives to speak one line you’ve practiced four thousand times, it's impossible to make that line sound normal. Next, I tried live radio theatre here in Loudoun County, Virginia. Radio Theatre is the LAZ-E Boy Recliner of theatre experience: no memorization, very little rehearsal, and no costumes, set, publicity or lighting. Go ahead and wear those polka-dot pajamas! Huge plus. But it has no audience, and that's a big, fat negative. So, after all those years I dared to "tread the boards" again and auditioned for a local production of Taming of the Shrew. I'd been hooked on Shakespeare ever since my third grade teacher, Mrs. Romito, cast me as "Lady Capulet" in Romeo and Juliet and explained to me and my best friends (who played Juliet and Nurse) what all the dirty jokes Nurse was telling Juliet meant. But in the modern day, after being Angel #2, I was hoping for at least two lines... while terrified to have too many. Respectful of my wishes, Director Tim Jon gave me a few lines… in four different roles. We began rehearsals that July with a cast from every conceivable walk of life who all had one important thing in common: no free time. Planning a rehearsal schedule takes the skill of an airline pilot (Coincidence our co-Producer and fellow actor, Stokes Tomlin, was a retired airline pilot?). Tough as scheduling turned out to be, the real "fly" in our ointment was a missing actor: our original "Hortensio" bowed out due to illness. But Tim Jon soldiered on, and we moved forward with no Hortensio at all. If you’re not familiar with Taming of the Shrew, Hortensio is a rather large role. He's the guy that winds up marrying The Widow. Did I mention one of my roles was The Widow? Soon it was six weeks from Opening Night and still no Hortensio. The cast and crew had called every actor we knew that fit the director’s description, which had by now narrowed to “Breathing" and "Possibly male”. Days ticked by. The Widow began having nightmares about history professors and polka-dot pajamas. Rehearsals were surreal, as half the time I was reading for Hortensio, too. You can sprain a muscle doing that. And that is why four weeks before opening night, I came to rehearsal deeply depressed. But acting is an amazing art: once practice begins, you somehow come to believe that everything will turn out. I easily lost myself in the beauty and humor of Shakespeare again, the movement and characterizations, and the overall thrill that is live theatre performance. Not to mention getting to work with great people like Tim Jon, who is one of my favorite directors, actors and mentors. Speaking of great directing, I’ll bet most folks think of acting as speaking lines. A good director will help you understand that acting consists of listening and reacting to each other’s lines. A great director will have you doing that every second you’re on stage, which pleases the audience no end. But you still have to be ready to save the day. So, when an actor forgets a line, you might be the very one needed to bring the scene back on track or, when a piece of the set falls down, help everyone stay in character - little things like that. In short, you hang together or die alone. As a result, you make friends for life with some of the most caring, intelligent, creative and generous people you’ll ever meet. And when you get together, you share stories like old war veterans... which brings us back to our missing Hortensio - and the theatre miracle. It was a lovely August night, and we were practicing our lines in the center of our soon-to-be-public-stage, the courtyard of Leesburg, Virginia’s Market Station - a cozy Globe Theatre-like space surrounded by excellent restaurants. At some point, a very tall, mustachioed fellow in a three-piece suit stepped out onto the balcony from The Tuscarora Mill Restaurant above us. Now, we were used to people watching rehearsals, so we proceeded show business as usual until he called down in a friendly tone. “So, what are you doing?” “Shakespeare!” we called up in unison. “Which play?” “Taming of the Shrew,” our Director, called up. The fellow nodded, stepped up to the railing and loudly, clearly and with great humor said, "You lie, in faith, for you are called plain Kate and Bonnie Kate and sometimes Kate, the Cursed! But take this of me, Kate of my consolation, hearing thy mildness praised in every town, thy virtue spoke of, and thy beauty sounded (though not so deeply as for thee belongs), I am moved to take thee as my wife!" We were dumbstruck at first, but as the man continued quoting lines from our play, we began to nod and smile among ourselves, and our Director - who looked as though he’d eaten the proverbial canary with cage - said, “And there’s our Hortensio". When the fellow was done, we applauded loudly and asked for more. He laughed and shook his head. “Funny. That’s not the response I usually get.” Then he said something about loving Shakespeare and launched into Hamlet’s soliloquy. So Tim offered him Hortensio on the spot, and, God bless him, he took it. Four weeks later we opened the show, and I’m pleased to say we sold out every night, few lines were muffed, no sets fell - nor any rain, nor any costumes - and Shawn Malone (who was co-manager of The Tuscarora Mill Restaurant back then), had a blast playing Hortensio and the audience loved him. Many years later Shawn confessed he'd come out to speak to us, because restaurant guests had complained about the noise. Well, God bless them, too.  POST SCRIPT Shawn is a fabulous actor who, I’m happy to say, has been in many, many performances since. My personal favorite is Ghost of Christmas Past in Once Upon A Christmas Carol (see 2018 pic below where he’s scaring the daylights out of Ebeneezer Scrooge). The other night, Shawn ran across a pic of Hortensio and The Widow at right and sent it over. He reminded me about the article I'd written so long ago, so I thought it was time to update and re-post here (The piece first appeared in my "Good Neighbor" column in Gale Waldron’s former Loudoun ART Magazine). In summary, if Shakespeare was correct and "All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players", theatre must be the best of all possible worlds. So, give it a try sometime. And be sure to look for me: I'll be the Director in the polka-dot pajamas. Once Upon A CHRISTMAS (above) is the award-winning musical adaptation of Dickens' classic tale: Music by Diane El-Shafey, Accompaniment by Carma Jones and Book Adaptation by Meredith Bean McMath.  Christopher Saunders as Scrooge's cheerful nephew, Fred Christopher Saunders as Scrooge's cheerful nephew, Fred "And I say... God Bless it!" Ebeneezer Scrooge's Nephew, Fred, explains the Christmas spirit to his Uncle Scrooge. Yes, there’s been a thousand Christmas Carol adaptations over the years - a lot of musicals, too. So why in the world would we - the creative trio of Diane El-Shafey, Carma Jones and myself - dare to write another? Because we knew they’ve all had one crucial storytelling element missing that we could bring to it… and in a way no had ever done before. For an hour and a half, ebeneezer Scrooge will go on a journey that leads to his redemption. And the audience is with him every step, because very scene will be woven throughout with unique characters and joyful, poignant and hilarious music - everything anyone needs to fall in love with the Charles Dickens’ classic all over again. And one thing more… In the year 2010, Diane and Carma sat down and wrote the musicm, and I adapted a script from A Christmas Carol to create a musical which Dolly Stevens of The Growing Stage produced at The Old Stone School in Hillsboro, Virginia. We tweaked it and tweaked it, and, in 2012, my company, Run Rabbit Run Theatre produced it, and I directed the show at the Franklin Park Arts Center in Purcellville. That production won a DC Metro Theatre Arts "Best of 2012" designation, along with Phil Erickson (Scrooge) as “Best Actor in a Musical”, Diane El-Shafey as “Best Musical Director”, and myself, “Best Director of a Musical”. We produced it again in 2018, and every show has had full houses and an enthusiastic response. So, how did we catch the true spirit of this story? Well, I've wanted to write a stage version of A Christmas Carol ever since I was a child. My family lived across the Potomac River from Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., and we attended A Christmas Carol there nearly every winter. I’d read the book many times, and, every time I saw the story performed, I knew something was missing. When I grew older and began to write plays, I finally put my finger on the problem: in order for an audience's to feel the full impact of the story, they needed to invest themselves in every character from the very start - especially Mr. Scrooge - and to do that, the audience needed to to feel more deeply about Scrooge before he became cold hearted. I didn't want audiences to simply hate Scrooge for his choices and be glad to see him suffer until he repents. That’s a shallow investment. I wanted them to care about the man, see the deep well of his loss and yearn for him to change. And I wanted audiences to see Scrooge yearn for that change, as well. By 2010, I'd been blessed to produce several musicals with Composer Diane El-Shafey and Assistant Composer and Accompanist Carma Jones. They complemented each other perfectly: Diane creating words and piano score, and Carma assisting with music and creating instrumental score. They were professional, and their musical range - from depth to charm - was astounding. During our years together, I'd been writing the historic fiction novels and (scripts) for original plays, adaptations and musicals and had become an award winning 19th century historian. I had a layered knowledge of 19th social behavior, dance, etiquette and folk music and that era’s unique humor. Yes, the audiences of A Christmas Carol needed to invest in the characters, but they also needed to invest in 19th century London! With all that, I knew I could bring things to A Christmas Carol no one else could - or ever had. After seeing an especially disappointing Ford’s Theatre stage production of A Christmas Carol in 2009, I called Diane and suggested we create a musical adaptation. As I began to explain why I had the audacity to approach such a task, we realized we were on the exact same page. When Carma said she was happy to join the project, we jumped right in. We began by looking at the story from a modern audience's perspective, pretending our audiences had never seen or read the story and knew nothing of 19th century London. We also looked at the tale from Charles Dickens' point of view. His 19th c. readers already understood the story's context: a London Christmas was a well-known quantity to them: the bustle of an English market place, the warm hearths and happy homes - nothing was knew. Watching Dickens push it away was horrifying to them, and we needed modern audiences to understand. Did we succeed? A reviewer put it this way: "McMath, who adapted the classic Dickens novel for the stage, and Diane El-Shafey, who wrote the production’s original score, have surrounded Scrooge with all the teeming life that fills London, or Loudoun, or any place with music — not just jingles that stick to the bottom of your shoe, but beautiful music that matters and makes sense.” - Mark Dewey, DC Metro Theater Arts, 2012 Now, Charles Dickens had chosen to start his story in Ebeneezer’s office as he’s rude to his poor assistant, Bob Cratchit. Next we see cold hearted Ebeneezer reject a request for donations, and lastly tell his cheerful nephew, No, he would not attend the party that night. Dicken’s 19th century readers knew the amazing good that even a small donation could do in poverty-stricken London, and they could easily imagine the wonderful dances and parlor games Fred had planned and Scrooge would miss, but modern audience need alllll those blanks filled in. And a musical can enrich their imagination and touch them in ways nothing else can. So we decided to start the show smack in the middle of a London Christmas Market, with a glorious song describing happy anticipation of Christmas Day. As Londoners sing, our audience sees all the baked goods and toys and hears laughter and flirtations alongside shouts of wide-eyed children. And every person there is a one-of-a-kind character whose words, action and song brings the moments of Christmas anticipation to life. For instance, the first time our audiences meet the charity workers who’ll visit Scrooge is as they pass through the generous crowd and the younger charity worker flirts with a Ribbon Seller. As the song plays on, we meet Scrooge's nephew, Fred, as he buys his Uncle the beautiful Christmas wreath he’ll soon try to give him. And in a little while, we meet Scrooge himself treating these delightful Londoners with utter contempt. Next, we go to Scrooge’s office - where Dickens started his book - and our audiences have a much deeper understanding of what Scrooge has chosen to reject. And that night, when the Ghost of Christmas Past, pulls Scrooge to back to his youth - to the Marleys’ party, just as the book describes, but we go further into Scrooge’s life: we see a kind and happy Scrooge playing parlor games and singing a romantic duet with his love, Belle. After the party - again, per the book - the young Scrooge will break off their engagement. But she sings “Belle’s Song” to him, begging him to come away from his greed. “The play's most poignant moment combines El-Shafey's beautiful music with Annie Stoke's [Belle's] beautiful voice and our own memories of the loves we've lost." - Mark Dewey, DC Metro Theater Arts, 2012 And the audience who had truly liked his young self is deeply struck by the loss of his soul.

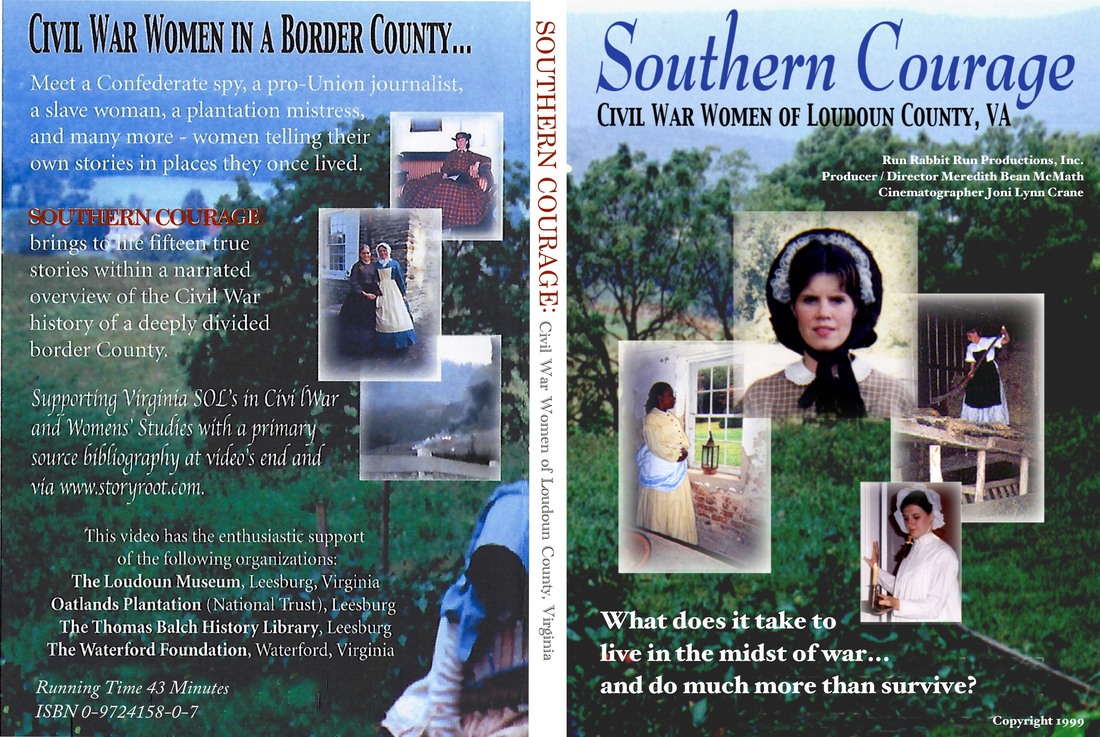

I once asked professional singer Annie Stokes (Belle... and half a dozen other characters in the 2012 production) about the musical, and she told me what she loved most about the show was the beauty of the music, and then the challenge and pure unadulterated fun of becoming a different character every time she stepped on stage. During the story’s journey, we remain accurate to the book, but the bold music and characterizations - 34 actors creating 125 characters - paint each scene in rich colors that flow all the way to the frame's edges. Our best reward has always been audience response - especially the children. Audience members told us they felt they were seeing Dickens' classic story with new eyes. And, just as our creative team hoped, A Christmas Carol, suddenly meant more to them. "McMath, who adapted the classic Dickens novel for the stage, and Diane El-Shafey, who wrote the production’s original score, have surrounded Scrooge with all the teeming life that fills London, or Loudoun, or any place with music — not just jingles that stick to the bottom of your shoe, but beautiful music that matters and makes sense.” - Mark Dewey, DC Metro Theater Arts, 2012 After all, as The Ghost of Christmas Present has said, “There is nothing in the world so irresistibly contagious as laughter and good humour!” I don’t trust people who present me with a list of rules. Tried and true methodology? Sure. Experience? Absolutely. But as soon as someone tells me it has to be done a certain way or it isn’t going to work/isn’t right/will fail, I balk. I balk, because experience has told me, art can’t progress unless you think outside the box. In my world, intuition and creativity always trump the rules. Always. Trust your creative instincts and work with people who trust their creative instincts, and you cannot fail. But the inherent freedoms that exist in the Art World naturally attract control freaks. They can't help themselves. They must create tidy rows. Your job is to FIGHT THEM... as politely as you can. STAY OPEN! You never know when inspiration will come to you. A walk through a hardware story can cause a set change that boosts the feel of an entire production. You can walk past an odd space and suddenly wonder if you could perform there. Meet a stranger and something tells you they’d be perfect for the next show. So you ask if they’ve ever thought about acting. Well they did act, in fact, a long time ago. And you cast them, and the audience goes crazy for them. Stay open! DREAM. And if something looks like it won't work, dream bigger. I have yet to be disappointed living life outside the box. As for Control Freaks, you have to be on your guard against... • The actor who tells another cast member how to say a line (Without fail, the worst, most insecure actor in the group); • The director who directs by humiliation (A person who consistently brings actors to tears shouldn’t be allowed to direct anything but traffic); • The crew member who says if it isn’t done exactly their way... Phhhffft. Creativity always has to trump control. And artists HAVE to trump control freaks, but, well... just remember to be polite.  McMath at her 2021 presentation at George Marshal International Institute, Dodona Manor, Leesburg, Virginia McMath at her 2021 presentation at George Marshal International Institute, Dodona Manor, Leesburg, Virginia From how to be an excellent actor or direct a riveting show, how to produce comedy or add depth to drama, great theatre has to begin with great stories. I’ve worked in theatre for over 45 years, learning from talented actors and directors and sharing this knowledge while Managing Director of the former Run Rabbit Run Theatre. Got my start when, just out of William and Mary, I was asked to create a public program for the Dranesville Tavern Museum. Soon found myself serving on the Board of Directors of the Loudoun Museum giving public presentations and programs. Then came writing columns and full historic fiction novels. But fellow Loudoun Museum Board Member Joni Lynn Crane and I started talking about getting the public to know previously unknown Loudoun County history. I was planning a living history presentation as part of the Elizabeth Carter Lecture Series at Oatlands Plantation in Leesburg, Virginia, and I was writing the script, collecting and creating the costumes and prepping the living history performers, Joni said, "Why don't we create a documentary?" Well, you'll need a company for that, so we founded Run Rabbit Run Productions, Inc. We edited Joni's film of the Oatlands presentation for our first documentary: "Having A Ball: Ballroom Costume Equiette and Dance in the Midst of the Rebellion”. Ken Burns’ Civil War Series had just come out, so we said, "Sure. Let's submit it!" Next thing you know, they'd accepted it. We were thrilled to see the History Channel air it several times in 1996. Our second documentary, "Southern Courage: Civil War Women of Loudoun County, Virginia", can be seen here. Researching for all of the above led me to begin writing plays in earnest, and my works now include original modern and historical plays, dramedies and comedies, and the books and librettos for musicals and operas. I've also become a prize-winning playwright, an award-winning historian, stage director and speaker. "One passion kept leading to another. I'm deeply grateful for the talented people I've worked with and for all the opportunities I've been given, but I do wish writers and directors were paid a little more..." Taylorstown, Virginia: February 20, 1863…

It was 11 pm, the party at the Filler home was well underway, and for once Mollie Anderson knew her brother was safe. Sgt. F.B. Anderson was a member of the only Union troop created in the midst of Confederate Virginia, and the Independent Loudoun Rangers were in constant danger because of it. Dressed in their very finest, the pro-Union young ladies of the neighborhood were busy dancing with the young men who'd come to call, among them Sgt. F.B. Anderson and another Loudoun Ranger. But out in the fields surrounding the Filler home, another sort of party was forming: a raiding party consisting of members of the 35th Confederate Cavalry Battalion. Commanded by Elijah V. White, the troop was nicknamed "The Comanches" for the fierce war whoop they yelled on the attack. And like legendary Confederate Colonel John Mosby, they enjoyed nothing better than to surprise the enemy. So, just after 11 pm, White's Comanches gave the war whoop and burst into the Filler home, and in the next few seconds, approximately twelve Confederate revolvers were leveled at Sgt. Anderson's head. The fellow in charge of the raid, a young man named Confederate Lieutenant Marlow, then informed Anderson that they would be taken to Libby Prison in Richmond. Everyone in the room knew Libby was a cesspool of starvation and disease, and sending Anderson to Libby would be tantamount to sending him to his death. So, at this, Mollie came to the young Confederate Lieutenant, threw her arms around his neck and began to weep as she begged him not to send her brother to Libby. In a society in which one never touched an un-gloved hand, let alone threw your arms about a stranger's neck, Mollie's actions were shocking. And what effect did this have on Marlow? An account written by Ranger Briscoe Goodhart in The History of the Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers simply says: "Marlow wilted." And when he rallied, he told Miss Mollie he would send her brother to a camp where he could be released on parole... but only on one condition: if she would dance the next set of dances with him. Mollie consented… and then things grew even stranger. As all the Confederate soldiers took partners and lined up for the dance, Sergeant Anderson walked over to the musicians, borrowed the violin, and begin to play, "The Girl I Left Behind Me." Lieutenant Marlow and Miss Mollie led off, and Marlow called for a "Promenade All" — typically the first dance of the evening. By this bit of ballroom etiquette, Marlowe was telling the crowd the Confederates were starting the party over. The Confederates stayed through 6-8 dances, and then they took Anderson and another prisoner away. As Goodhart put it, "It was hard to tell who was the hero of the evening." Lieutenant Marlow did parole Sgt. Anderson the next day, and Anderson dutifully signed in to Camp Parole”in Maryland and was eventually exchanged to return to his unit. So was the Civil War truly this Civil? No. As the war progressed and Loudoun County was torn to shreds, the Filler Ball would never be repeated. VIRGINIA'S ONLY UNION TROOP With two-thirds of the County pro-Southern and another third either Quaker or pro-Union, the border County of Loudoun was a breeding ground of conflict like no other. The Independent Loudoun Rangers were formed June 20, 1862 under Quaker-turned-Captain Samuel Means, and would go down in history as the only Union troop ever formed on Virginia’s soil. Members of this cavalry troop were drawn mostly from Germans and Quaker families. The Germans who settled Taylorstown and Lovettsville (then known as Berlin) had come down from Pennsylvania and retained a pro-Northern, anti-slavery attitude. The Quakers who founded Waterford, Hamilton (then Harmony) and Lincoln were pro-Union, anti-slavery and decidedly pacifist, but when war came to their very doorstep, things changed. Many Quakers became willing to be "written out" of the Church to join the Union Army. From the start, the Rangers knew what they were up against. Surrounded by pro-Confederate households and Confederate troops, they knew their enemy well. The men of the Loudoun Rangers and White's 35th Battalion had grown up together and many were former friends and schoolmates…. even brothers. Two, Charlie and William Snoots split as they joined up — William signing with the Comanches and Charlie with the Rangers. And now Charlie and William waited for the day they'd face each other on the battlefield. As Loudoun is a relatively small county, it was a short wait. Just two months after the Rangers' formation, about 23 members of the new troop set up makeshift headquarters at the Waterford Baptist Meeting House and bedded down for the night on the long wooden pews. In the early morning hours of August 27, the Rangers were awakened by loud noises. They tumbled out of the church and formed a line in front of the Church's plaster and lath vestibule. Luther Slater, the Lieutenant in charge that night, called out, "Halt! Who comes there?" The only answer was a tremendous volley of short-range pistol fire from members of Elijah V. White's 35th Battalion. The Comanches had slipped passed the Rangers' pickets and come through the cornfields to meet their prey. The Rangers returned fire as they retreated back into the church through the wood vestibule, but the Confederates continued firing, and Goodhart tells us, "The bullets poured through this barrier as they would through paper." After several hours of fighting, two Rangers had died and half the men lay wounded in the pews. Lieutenant Slater was suffering from five wounds, several taken at the first volley. Goodhart noted that, by the end of the fight, the place looked "more like a slaughter pen than a house of worship." Eventually the Rangers were forced to surrender. As the prisoners filed out of the church, one Comanche, William Snoots, watched closely to see if his brother Charlie was among them. Charlie had indeed been in the church and exited without a wound. When William saw Charlie alive and well, he made a move to shoot him, but Goodhart says William was, "fittingly rebuked by his officers for such an soldierly and unbrotherly desire". Charlie was left unscathed. Soon after this fight, the Rangers had a small success in the town of Hillsboro. There they surprised, then took prisoner a few members of White's command, along with some valuable equipment and arms. But the Rangers' joy was short-lived. On September 2, a group of Rangers rode into Leesburg and ran into another Confederate Unit, the 2nd Virginia Cavalry. Seeing the disadvantage of engaging the enemy within a highly pro-Confederate town, the Rangers quickly reformed north of the city at Mile Hill on the Carolina Road (now Route 15). With numbers greatly in their favor, the Confederates rode north to meet the Rangers and soon outflanked and surrounded them. As the Rangers fought to break free of the line, the fight dissolved into a battle of sabers. Many escaped - but with sword wounds. With one dead, six wounded and several prisoners taken, this second battle came close to destroying the Rangers completely. Only 20 cavalry soldiers remained, but they pressed on. Each had made the choice of principle over place, love of country over old friendships, and conscience over the bonds of blood. While it's Briscoe Goodhart's contention the two early defeats, "did to a very large extent interfere with the future usefulness of the organization," the cavalry unit eventually grew to 120 in number and went on to fight a battle at Harpers Ferry, participate in the Battle of Antietam and the Gettysburg campaign, and made themselves useful to the Union Army by successfully carrying dispatches and scouting their old neighborhoods. In April of 1864, the Rangers found out several members of the 35th Battalion would be at a dance being held at Washington Vandeventer's home near Wheatland. Perhaps it was payback for the humiliation Anderson suffered the year before, but he and another Ranger led the attack. Unfortunately, the Confederates were ready for them, and they were immediately engaged in a skirmish. Eventually the Rangers pushed the Confederates back and out of the house, and the battle soon ended as they made their escape. In the end, the Rangers had shot and killed an 18-year old Confederate soldier named Braden and slightly wounded his sister. The Confederates were not likely to forget the incident, nor Sergeant Anderson. In late November of 1864, General Sheridan decided to burn out the “bread basket of the Confederacy," i.e. The Shenandoah Valley and much of western Loudoun County. The Union Army was ordered to "consume and destroy all forage and subsistence, burn all barns and mills and their contents, and drive off all stock in the region." Sheridan hoped one byproduct of the raid would be the destruction of the Confederate citizens’ morale (the Burning Raid was so successful on both counts that General Grant gave General Sherman permission to take the concept south in his famous "March to the Sea"). Before the Raid, the Union Army thought that, with first-hand knowledge of who'd still have cattle or wheat in the barn, it was logical to ask the Loudoun Rangers to lead the burning parties. They did their duty but few were proud of their part in this “scorched earth” policy. After all, the soldiers' main source of resistance to their efforts was the anguished tears of women and children begging them not to burn their barns or kill the livestock. For the Confederate households, the Burning Raid meant no food for the winter, and for the Quakers, it meant the loss of all their goods despite their constant and adamant support for the Union cause. Small wonder Briscoe Goodhart book on the Loudoun Rangers gives scant space to the "Burning Raid." THE LAST DANCE By Christmas of 1864, there was hope among Unionists that the war would soon end, but in Loudoun, the residents were more divided than ever. On Christmas Eve, the Loudoun Rangers were visiting their families, and Anderson's mother decided to a party at their home near Taylorstown. One of their guests that night was a young lady that, rumor had it, would soon be Anderson's bride. But outside the home, sixteen Confederate cavalrymen — some with the 35th Battalion and some with Colonel Mosby's troops — gathered for yet another raid. Ten soldiers drew their revolvers and entered the Anderson residence. Anderson must have known they would rather kill than arrest him, so he drew his revolver and rushed to the back door. But he'd removed his sword in order to dance that night, and in a tragic twist of fate, the S-hook of his sword belt caught a chair, and the chair caught him fast in the doorway. He was trying to detach himself as the soldiers opened fire, and he was shot four times. His mother mother caught him as he fell, and he died in her arms a few minutes later. In April, peace finally came — or at least a lack of outright war.

And when the Loudoun Rangers were mustered out of service, they'd lost a third of their number. The vast majority of survivors had suffered wounds in battle or starvation in Confederate prisons. But, through it all, each to a man remained true to the Union cause and thereby earned the honor of being the only Virginians to serve the Union Army. But no one could blame them if, at every dance they attended in the years to come, they watched the dance hall doorway rather than their partners' toes. This post first appeared as “A Hard History: The Union Soldiers of Virginia” in the former LOUDOUN MAGAZINE, 2011. The serious brain malfunction began when I was 56. Not just, "Oh, I'm having a bad day", but a "Oh, I can't read English for 3 hours" day. I began telling my friends, family and doctors that it felt as though my brain was broken. Yes. That seemed right. Because up until that year I'd been a high-energy, multi-tasking little success story who'd been a published author, an award winning historian, and a prize-winning playwright who loved the challenges each day brought me.

Their response? They just told me that it was natural. I was depressed. "You just lost your mother, your son moved to the west coast, you've had to move from the beautiful home you spent 32 years restoring (another story, entirely) , and you had to shut down your highly successful business in order to pack things up.” Well, I had an inkling our son would move soon, but my mother’s death was quite sudden, and I had no idea that, after she passed, we would suddenly have to move. Just never occurred to us to plan for that. Yes. All worthy of severe depression. But could depression have this much power over my ability to simply think? I’m a writer and a producer, but I suddenly had days I could not READ a sentence, let alone write one. And at other times I couldn’t speak clearly. Could depression do all of that? Or was I going crazy. Could crazy do this to a brain? I kept trying to tell myself "Brain depressed". And my mind kept saying, "Brain broken". And then there was the morning my husband found me hunched over my computer - just where he'd left me the night before. “Have you been there all night?!” “Yes." “What are you doing?!?” “I can’t get these sentences right.” I had been re-editing the same two sentences all night long. So I went to the doctors again, and they said, "Nothing more than depression. Would you like anti-depression medicine?" "No," I said and when back home to things to do, boxes to pack, a house to sell, and a life to move forward any way I could. Then one day I began to cry. I began to cry hysterically and couldn't stop myself. I could not think. I was terrified. My husband, Chuck, was driving to work, and I called him. I said "Help me, please. Don’t make me hurt myself to prove to you I need help!” (Let’s just pause and let me make this clear: I was not suicidal. I was desperate). My brain – that thing other people once called clever, well-organized, and highly creative – simply wasn't working anymore. I couldn't trust it, and neither could anyone else. And how do you explain what you're dealing with when the correct words won’t come to you anymore? Depressed? Well, yeah. You’d be depressed, too, if your thoughts could no longer walked in a straight line. Thank heaven Chuck took me at my word, turned around and came home to drive me to Urgent Care. There I "spoke" to a psychiatrist who suggested I go to the hospital for further study. "Yes," I said. "I will do anything to try to understand what’s happening to me" And they sent me to the Pysch Ward of the nearby hospital. I remember the trauma of being rolled into that ward in a wheelchair and riding passed people whose eyes stared straight ahead at nothing and whose feet shuffled aimlessly. These people were zombies. This was where I was coming to have someone look at my brain and help me? These people didn’t appear to be having their brains evaluated and fixed. They looked like they were having their brains permanently fixed in one position. And is this what I would become? The rest of the day is a vague memory that ended in the afternoon when my husband came to see me. Right away I told him, “I don’t belong here. I know I don't belong here. I want to go home. Right now.” My poor husband. But because I’d signed in voluntarily, I was able to sign myself out, and we went home. Thank god. After that, I made myself be calmer. I would do whatever it took to avoid going back to the place where the zombies walked. There was one more long, terrifying year of coping with a broken brain and with doctors who constantly swept it all aside before I finally had the Grand Mal seizures. I’d been prepping for a colonoscopy – dreaded things – with a 2-day liquid diet that apparently depleted whatever I had left that was fighting this thing. I went to bed the night before with the colonoscopy scheduled in the early morning. When I was starting to fall asleep, I remember seeing something like death walking toward me, ready to take me with him. And I felt a strange calm. Death would finally mean peace. I did not wake my husband and tell him any of this. What would be the point? There was nothing he or I could do. Instead I told myself, I’ll go for the procedure in the morning, and then I’ll feel better and perhaps this will pass. But if death takes me tonight, that's all right, too. I can only remember one thing about that night: violently throwing off my covers and jamming my husband in the back with my hand – something I’d never done before and never done since. I apologized. He mumbled it was alright. And apparently later in the night, I swung violently out of bed with my first Grand Mal Seizure. The thump of my fall woke my husband, and he called the rescue squad. I had one more seizure at home and the last one at the hospital before they finally did an MRI to try to evaluate my brain - my broken little brain. When I woke up late the next morning - flat out in a hospital bed - I assumed I'd had the colonoscopy. There were people – male nurses - lifting me up and removing a bedpan from under me, while one was saying, “I hope you don’t mind the lack of privacy". My cheerful, highly medicated self replied, “No problem! You’ve all already seen everything!” And as the bedpan came away I added, “Now that’s service!”. But they didn’t laugh. See, I didn't remember anything about the seizures. I decided these nurses were the ones who’d done my colonoscopy, and that the medication caused me to forget getting there that morning. But I did think it was strange that I couldn’t remember anything about getting there. Once they left the room, my husband came in and explained. He told me how he was wakened by the sound of my fall. Described my first Grand Mal to me, and my second as the ambulance came to get me (But he was kind and did not describe them in great detail). And, you know what? The first thing I felt was relief. My broken brain had finally given a huge, very tangible, very measurable sign of its brokenness. I could finally shout at my doctors, “I TOLD YOU MY BRAIN WAS BROKEN!" And, yes, the seizures did wake up my doctors. I never had to hear the words "You're just depressed" again. Instead they cried as one, “AH! She really is physically sick! Look, here is something we can treat! Maybe even diagnose correctly now!” And I was so relieved. I finally knew what was happening. Still didn’t know why, but… that would come in time. Oh, and it did take time - a long time. But the doctors finally figured it out: first they said it was because of my autoimmune disease: Antiphospholipid Syndrome. It has a tendency to cause blood clots (the thing that made my having children so difficult as it created blood-clotting in the placentas). But they couldn't find any blood clots in me. Hmmm.... And, sad to say, my first Neurologist was an idiot who put me on the standard anti-seizure medicine Keppra, gave me a 1-hour EEG 30 days after my first Grand Mals, and said, "You like fine!" So he took me off the Keppra, and I woke up in the hospital 2 days later after another Grand Mal. I was put back on Keppra as we went looking for a Neurologist who knew something - someone who focused on Epilepsy. We found a brilliant Doctor who's an Epileptologist, and I got back to most of a life. Brain fog still came and went, but nothing like it was during those 2 years. My brain no longer felt broken, more like... sprained. I hobbled as I walked about. But over time I learned Keppra can give some of us hideous side effects: mood swings that'll have you crying one minute and screaming the next. And since my husband had already gone through enough hell - after I put a serious dent in our dishwasher - I asked my Neurologist to switch my meds to something less damaging. I've been on Lamactil (Vimpat) 7 years. It gives me headaches, awful rashes and it's still possible for me to have Focal Seizures, but I'll live. And my new doctor began to focus on the fact that I have Hyponatremia – chronic low salt. Truth is, if anyone's salt becomes severely low - any one in the world - they can have a seizure. Acceptable low salt level is 134, but my salt was 122 the night I first seized and 125 after my next big seizure a month later. I'm 65, now, and still trying to get the right balance between my low salt, water, and the anti-seizure medicatoin (which can damage me if I don’t have enough water). My GP finally said "Try Gatorade instead of water", and that was doing a nice job... until I had a Focal Seizure. We switched to Liquid IV instead of water, which was fine but bloody expensive. Now I just have water and then one bottle of Liquid IV a day I still have memory issues, but the misfires are due partly to anti-seizure med and mostly due to flat out having Epilepsy. Seizures do damage and some of it is permanent. My friends try to be nice. When I can’t recall a certain word, flip words or suddenly can’t remember the name of someone I’ve known 30 years, my friends will say, “Oh, that happens to all of us!”, I just smile. I’d rather have them chalk it up to something they can relate to and what’s the point of my saying something snappy like, “Really? Ever forgotten your own birth date?” The bad news is I have second trigger for seizures: stress. I don't have Grand Mals. I have these smaller things called Focal Seizures and they are purely due to Epilepsy. Unlike Grand Mals, focals do not cause physical jerks. More like having your mind just up and walk away from your brain. If I can feel it coming on and think clearly enough, I'll take an Ativan (A peaceful little drug). But one time I felt my brain disassociate and got to a chair just before I blacked out. When my husband came home, apparently I began talking to him (I don't remember any of this). I made no sense. Eventually I came back to full consciousness, and we set up an appointment to see my Neurologist. He explained to us that stress - pure stress - can cause seizures, and I needed to change my lifestyle. I'd been stressed out doing Board work for a nonprofit board, so I pulled myself away. Oh, and in my state - Virginia - you can't drive a car for 6 months (for obvious reasons). So that was another reason to stop what I was doing. But I kept my production company. I wasn't ready to give it up. I loved it too much. Another small focal showed up the day I woke up and my husband and I began to make the bed. I would begin a sentence. The first half would make sense, but I could not make the second half make sense. The words I went looking for simply weren't there for me. They were replaced by nonsense. But this was a tiny incident past, and I didn't bring it up to the Neurologist. Next focal seizure was a big one, and for that I was once more completely conscious. And it scared the hell out of me. Here's my summary of the experience: September 10, 2021 – Been a hard week. I contracted a stomach virus and had diarrhea for 3 days. Then, just as I was getting over it, I had a Focal Seizure. Hadn’t had a seizure in a year and a half! Chuck and I had been watching “The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society”, and I fell asleep or lost consciousness for a bit. Then I heard Chuck ask me a question about the scene we’d just watched, and I wanted to answer him. Here’s how it went (From Chuck’s MP4 video). Apparently, this was about half-way into the conversation: I said, "That was part of the original thing about the area" when I was trying to say, This is the kind of thing that happened during World War II. "She’s the woman who’s out of person is saying bad things about the stuff," but I meant, Elizabeth is tending to the young woman dying and showing how horrible things were - to have a young woman die of wounds while having a baby. "But we don’t know what she’s basing it on" (We don’t know if it’s a true story). "She was talking to us to… she was important on this" (The woman who died was important to the story, but – and I never got this part out - she was not Elizabeth, the lead, so we don’t know her name). Then Chuck began to stop me and tell me I sounded like I had the other time I wasn’t making sense. "What are you talking about, Charlie?" At that point, I couldn’t remember what a Focal Seizure was or that I was capable of having one. Chuck explained I’d been talking around and around in circles. "Well, I got very sleepy and I went out of sleep" (I was trying to explain say I’d just been sleepy, and I spoke to you right as I was coming awake). Then he reminded me about the last seizure I’d had that was like this and asked me if I felt okay. "I… don’t… I, I think I am." (I actually wanted to say No) And this is where the video stops. Soon after, I became fully conscious and able to speak clearly, again. The next day I took this event apart. Here goes: During the last part of this seizure – probably around the time I realized Chuck was filming me - I knew I was trying to find the words and couldn’t reach them. I would begin a sentence and hear that the words coming out of my mouth were not the ones I had in my head. I was having a Focal Seizure, where the brain waves that connect the part of the brain that stores words with the part of the brain that puts sentences together wasn’t working (as explained by my Neurologist). The bridge was broken. When you have a seizure, it shows up on an EEG via brain waves that go crazy. No peace. No way to connect. And during the seizure, I eventually realized something wasn’t working and that it was that condition I had. I wanted to remember the name of that condition but couldn’t think of it. Around this time – as I was coming into consciousness - I also became terrified, because I had no idea when or if the disconnect would end. At that point, I’d only had one Focal before, and I couldn’t remember much about it other than the speech problem. I started worrying what would happen if my ability to speak never returned. Was my life over? Would I need to be put in full-time care, because I could no longer communicate? In the video, it’s obvious I’m scared. My brows are furrowed in confusion. My eyes would go wide. At one point I flail my arms a bit. At another time, I curl my hands. I think I was seeing if these movements would help me find the words. They didn’t. But, when I did the curl, I remember thinking something along the lines of, “Okay, I can still make my hand do this if I want! I can control it!” When I began to remember more about my problem, it occurred to me I had two problems; two names? But I couldn’t ask Chuck ‘cause I couldn’t make sense, and I thought maybe I could work this out myself. Maybe I could look them up somehow. Maybe the act of typing would bring it to mind (Hey, it’s happened before when I’m at a loss for words!). So I looked at my iPad and knew I could do research there – somewhere in that blank top line (I must have had Google up). But I didn’t even know how to start typing. And my ability to research was wiped clean. My brain was empty. But I kept “coming to” (The neurons between word storage and sentence generation began to calm down and reconnect). Finally occurred to me one of my conditions was called APS. I was able to type APS on the top line of the iPad and found it meant Anti-phospholipid Syndrome. Okay. But I knew that wasn’t why I was having trouble speaking. Then I remembered seizures – Oh, right. I have Epilepsy. Okay. Got it. Got them both, now. And I’ve had another Focal Seizure, and I’m coming out of it. I’ll be okay. But all that took a long time to remember, damn it. As an aside, while I was trying to answer Chuck, at some point I became aware he was videotaping me. And that was... incredibly creepy. He was smiling slightly – like he was amused by my incoherence. And the film felt like an intrusion. But I did not tell him this. Looking back on it, I think his smile was a coping skill. I realize this is an awful lot to deal with… I later appreciated having the video. Not that it’s going to change anything about my situation, but I do like knowing what I’m experiencing... and what Chuck’s experiencing (poor guy). And I liked figuring out how what I said related to what I tried to say. It was kind of a fun exercise. So, “Coming out of sleep” means “waking up”. Okay, that almost makes sense. The weirdest thing was knowing exactly what I wanted to say, and having everything coming out of my mouth pure babble. That just wasn’t as clear on my first Focal. During my first Focal, I really thought I was making perfect sense! Looking back on all this, I realize I’ve actually had a third incident - after my Grand Mals but before my first big Focal. Chuck and I had just “come out of sleep”, and we were making the bed. I was joking around and began to realize the first half of my sentences made sense but the second halves made none. The whole thing passed very quickly, thank God, and we laughed about it. We just chalked it up to my weird, new brain due to Grand Mals. And I've had a few smaller ones since then, too. But after "film night", I had to decide whether to tell Dr. Kurukumbi and risk being unable to drive for 6 months. I hadn’t lost consciousness, and it was just my language, so…. Then my son (who lives with us right now) suggested perhaps I’d had a Focal, because, after 3 days of pure diarrhea from the stomach virus I was just getting over, my body had not been able to process enough of my anti-seizure medicine. Also wasn't able to retain the salt I needed! Bingo. He was absolutely right. And then a big decision: to be safe, I shut down my business entirely. This was to keep myself from constantly feeling like I should be DOING SOMETHING. That I needed to get better so I could back to work. And made me feel incredible stress. And sorry as I am to be in forced retirement, I am so thankful I don't have anything to do any more. So, I don't have Grand Mals. But, given stress or illness, I can have focal seizures - conscious or unconscious - and I can speak through both and make no sense whatsoever. So, after all this, what have I taken away from my two years of brain fog and the next 6 years of learning to deal with Epilepsy?

In dealing with all of the above, I’d say the very worst thing about having epilepsy is losing memories. That's a loss I do mourn over quite a bit. I'm glad I've always kept diaries of one sort or another, and I'm glad I've kept thousands of photos. It helps... quite a lot. But I also mourn the fact that I no longer speak and write with ease. I’ve been a storyteller from the day I could talk, and my life and life’s work – all of it - depends on memory. It’s what you need to be able to write. My stories that always start from my memory are hard to come by, and I mourn the loss of the success I was about to have. Before seizures, I spent two years in confusion, unable to write or organize anything. And I had just written the libretto for a critically acclaimed opera. My opera – the one for which I wrote the concept, story line and libretto after years of research, and everything about the work was excellent. Lucky enough to partner with the brilliant composer David E. Chavez. And the ability to do something like that was suddenly gone. Now I could barely write a sentence. And I had no idea whether any of it would come back. It slowly did. Not all of it. But most of it – enough to function and restart some of my writing, play writing, and marketing, etc. … because I learned how to help it come back. Then losing weight, eating properly, and daily exercise have all helped sharpen things. In fact, when I’m thinking a unclearly, I’ve learned to ask myself, Have you exercised today? More often than not, the answer is No, and I get up and start walking (Now I’m addicted). And here I am, working hard to stay grateful for every minute on the planet... and getting more and more used to surprises. |