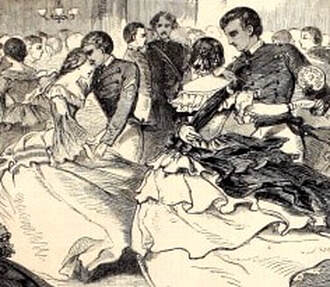

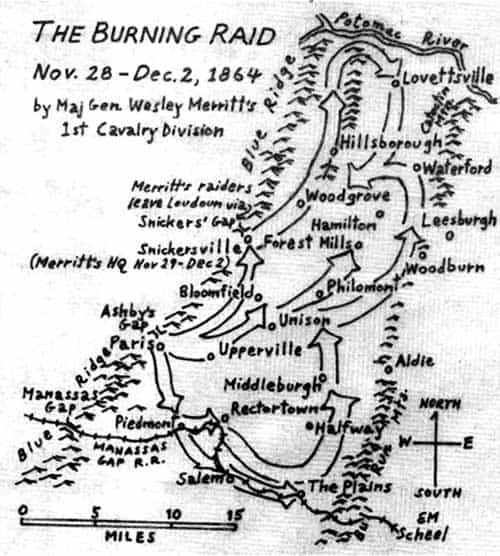

by Meredith Bean McMath  Taylorstown, Virginia February 20, 1863… By 11 pm, the party at the pro-Union James Filler home in Loudoun Country was well under way. Among the guests was Union Cavalry Sergeant F.B. Anderson, a member of the Independent Loudoun Rangers - the only Union troop ever formed within the confederacy. Sergeant Anderson's sister, Mollie, was also there that night and no doubt pleased to know her brother was safe for the evening. But, out in the fields around the home, another sort of party had formed: a Confederates from the 35th Confederate Cavalry Battalion. Commanded by Elijah V. White, the troop was nicknamed "The Comanches" for the fierce war whoop they yelled during an attack. And like legendary Confederate Colonel John Mosby, they took pride in surprising the enemy. And a few minutes after 11 pm, White's Comanches gave a war whoop and burst into the Filler house. In the next few seconds, around twelve revolvers were leveled at Sgt. Anderson's head, and the fellow in charge of the raid, Confederate Lieutenant Marlow, informed Anderson he would be taken to Libby Prison in Richmond. Libby Prison was well known as a cesspool of starvation and disease, and sending Anderson to Libby was tantamount to sending him to his death. So, when Marlow gave his edict, Anderson's sister, Mollie, came to the Confederate Lieutenant, threw her arms around his neck and began to weep as she begged him not to send her brother to Libby. In a society in which one never touched an un-gloved hand, let alone throw their arms around a stranger's neck, Mollie's action was a shock. And what effect did this have on Marlow? In Ranger Briscoe Goodhart's The History of the Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers, he simply said, "Marlow wilted." Marlow told Miss Mollie he'd send her brother to a camp where the soldier could be released on parole... but only on one condition: if she would dance the next set of dances with him. Mollie happily consented. Then things grew even stranger.  All the Confederate soldiers decided to take partners, as well. And, as they lined up for their first dance, Sergeant Anderson walked over to the musicians, borrowed a violin, and began to play, "The Girl I Left Behind Me." Then Marlow called for the "Grand March". This was usually the first dance of the evening, so Marlow was telling the crowd the party was starting over. The Confederates stayed through 6 or 8 dances, and then they took Anderson and the other Union soldier away. As promised, Lieutenant Marlow paroled Sgt. Anderson the next day, and Anderson dutifully signed in to Camp Parole in Maryland. He was eventually exchanged to return to his unit. But, as the Civil War progressed and Loudoun was torn to shreds by war, the charming compromise found at the Filler residence would never be repeated. VIRGINIA'S ONLY UNION TROOP With two-thirds of the County pro-Southern and another third either Quaker or pro-Union, the border County of Loudoun was a breeding ground of conflict. The Independent Loudoun Rangers were formed June 20, 1862 under the Quaker-turned-Captain Samuel Means, and they've gone down in history as the only Union troop ever formed on Virginia soil. Members of the troop were drawn mostly from Germans and Quaker families. The Germans who settled Taylorstown and Lovettsville (then known as Berlin) had moved to Loudoun from Pennsylvania and retained their pro-Northern, anti-slavery attitude. According to their faith, the Quakers who founded Waterford, Hamilton (then Harmony) and Lincoln were anti-slavery and therefore pro-Union. They were also decidedly pacifist. but when war came to their doorstep, things began to change. Many Quakers chose to be "written out" of the Church to join the Union Army. From the start, the Rangers knew what they were up against. Surrounded by pro-Confederate sentiment for years, they knew their enemy well. The men of the Loudoun Rangers and White's 35th Battalion had grown up together and many were former friends and schoolmates…. and sometimes brothers. Charlie and William Snoots split as they joined up — William signing with the Comanches and Charlie with the Rangers. And now Charlie and William waited for the day they'd face each other on the battlefield. As Loudoun is a relatively small county, it was a short wait. Two months after the Rangers' formation, about 23 members of the new troop set up makeshift headquarters at the Waterford Baptist Meeting House and bedded down for the night on the long wooden pews. In the early morning hours of August 27, the Rangers were awakened by loud noises. They tumbled out of the church and formed a line in front of the Church's plaster and lath vestibule. Luther Slater, the Lieutenant in charge that night, called out, "Halt! Who comes there?" The answer was a tremendous volley of short-range pistol fire from members of Elijah V. White's 35th Battalion. The Comanches had slipped passed the Rangers' pickets and come through the cornfields to meet their prey. The Rangers returned fire as they retreated into the church through the wood vestibule, but as the Confederates continued firing, Goodhart tells us, "The bullets poured through this barrier as they would through paper." After several hours of fighting, two Rangers died and half the men lay wounded in the pews. Lieutenant Slater was suffering from five wounds - several from the first volley. Goodhart noted that, by the end of the fight it was said the place looked "more like a slaughter pen than a house of worship." Eventually the Rangers were forced to surrender. As the prisoners filed out of the church, one Comanche, William Snoots, watched closely for his brother Charlie. Charlie had indeed been in the church and exited without a wound. When William saw Charlie alive and well, he made a sudden move to shoot him but, Goodhart says, William was, "fittingly rebuked by his officers for such an soldierly and unbrotherly desire". And Charlie was left unscathed. Soon after this fight, the Rangers had a small success in the town of Hillsboro (Then Hillsborough) on Charlestown Pike, where they surprised a few members of White's command and took away prisoners along with some valuable equipment and arms. But the Rangers' joy was short-lived. On September 2, a group of Rangers rode into Leesburg and ran into another Confederate Unit, the 2nd Virginia Cavalry. Seeing the disadvantage of engaging the enemy in the middle of a highly pro-Confederate town, the Rangers quickly reformed north of the city at Mile Hill on the Carolina Road (now Route 15). With numbers greatly in their favor, the Confederates rode north to meet the Rangers and soon outflanked and surrounded them. As the Rangers fought to break free of the line, the fight dissolved into a battle of sabers. Many escaped but with sword wounds. With one dead, six wounded and several prisoners taken, this second battle came close to destroying the Rangers entirely. Only 20 cavalry soldiers remained, but they pressed on. Each had made the choice of principle over place, love of country over old friendships, and conscience over the bonds of blood. They would fight on. While it's Briscoe Goodhart's contention the two early defeats, "did to a very large extent interfere with the future usefulness of the organization," the cavalry unit eventually grew to 120 in number and went on to fight a battle at Harpers Ferry, participate in the Battle of Antietam and the Gettysburg campaign, and made themselves useful to the Union Army by successfully carrying dispatches and scouting throughout their old neighborhoods. And, in April of 1864, the Rangers found out several members of the 35th Battalion would be at a dance being held at Washington Vandeventer's home near Wheatland. Perhaps it was payback for the humiliation Anderson suffered the year before, but Anderson and another Ranger led the attack. Unfortunately, this time the Confederates were ready for them, and they were immediately engaged in a skirmish. Eventually the Rangers pushed the Confederates back and out of the house, and the battle soon ended as they made their escape. In the end, the Rangers had shot and killed an 18-year old Confederate soldier named Braden and slightly wounded his sister. The Confederates were not likely to forget the incident - nor Sergeant Anderson who led the attack.  In late November of 1864, General Sheridan decided it was time to burn out the “bread basket of the Confederacy," i.e. the Shenandoah Valley and much of western Loudoun County. The Union Army was ordered to "consume and destroy all forage and subsistence, burn all barns and mills and their contents, and drive off all stock in the region." Sheridan hoped one byproduct of the raid would be the destruction of the Confederate citizens’ morale (In fact, the Burning Raid was so successful on both counts, General Grant gave General Sherman permission to take the concept south in his famous "March to the Sea"). Just before the Loudoun's Burning Raid, the Union Army thought it was logical to ask the Loudoun Rangers to lead the burning parties, because they'd have first-hand knowledge of who'd still have cattle or wheat in the barn, Well, they did their duty, but few were proud of their part in this “scorched earth” policy. After all, the soldiers' main source of resistance was the anguished tears of women and children begging them not to burn their barns or kill the livestock who were starving. For the Confederate households, the Burning Raid meant no food for the winter, but for the Quakers, it meant the loss of all their goods despite their constant, adamant support of the Union cause. Small wonder Briscoe Goodhart book on the Loudoun Rangers gives scant space to the "Burning Raid."  THE LAST DANCE By Christmas of 1864, there was hope among the war was winding down - would soon end in peace, but in Loudoun County, Virginia, the violence was unremittent. On Christmas Eve, the Loudoun Rangers were visiting their families, and Anderson's mother decided to a party at their home near Taylorstown. One of their guests that night was a young lady that, rumor had it, would soon be Anderson's bride. But outside the home, sixteen Confederate cavalrymen — some with the 35th Battalion and some with Colonel Mosby's troops — gathered for yet another raid. Ten soldiers drew their revolvers and entered the Anderson residence. Anderson must have known they'd rather kill than arrest him, so he drew his revolver and rushed to the back door. But he'd removed his sword in order to dance that night, and in a tragic twist of fate, the S-hook of his sword belt caught on a chair, and the chair caught him fast in the doorway. He was desperately trying to detach himself as the soldiers opened fire. Shot four times, his mother mother caught him as he fell. He died in her arms a few minutes later. And in April of 1865... peace.

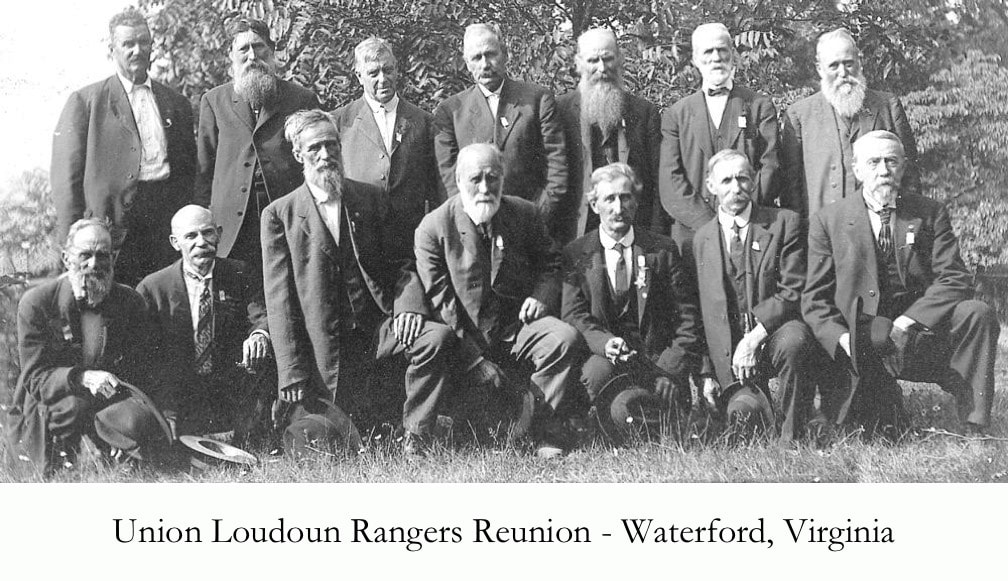

When the Independent Loudoun Rangers mustered out of service, they'd lost a third of their number. The vast majority of survivors had suffered wounds in battle or starvation in Confederate prisons, but, through it all, each had remained true to the Union cause. And the Company earned the honor of being the only Virginian soldiers to serve the Union Army. But none could blame them if, at every dance they attended for all the years to come, they watched the dance hall doorway rather than their partners' toes.

This McMath article first appeared in the former LOUDOUN MAGAZINE, 2011.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |