|

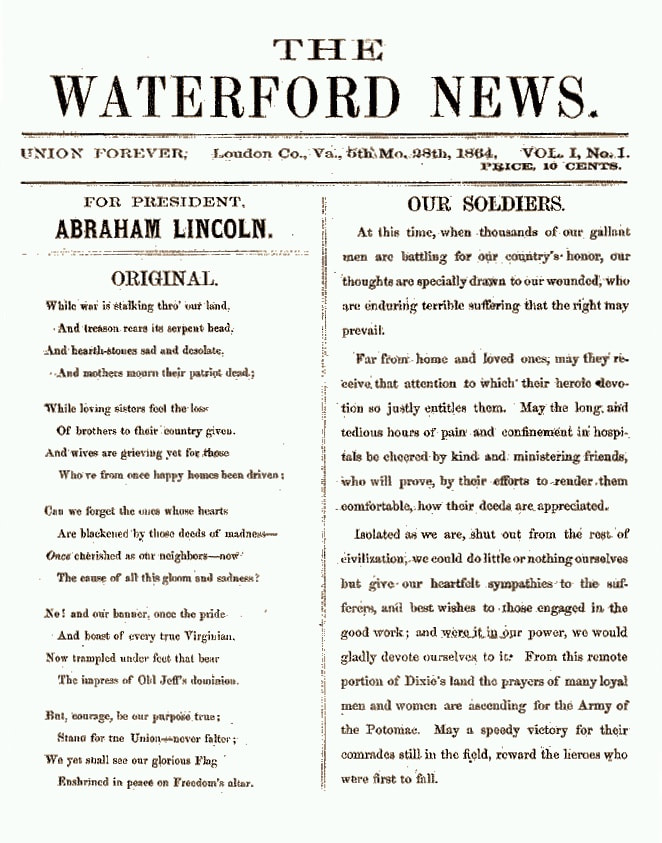

Wanted -- A Union commander, to take charge of the Rebel Conscripting Officers. Wanted -- A plaster for the [Second Street] mud-hole, it is breaking out again. Wanted -- A straight-jacket for the Editor, who was bent on having her own way. The Waterford News - 11 Mo. 26th, 1864, Vol. I, No. 6 In 1864, a young woman of Waterford, Virginia named Lida Dutton decided providing meals to Union soldiers and helping the wounded was not enough. She had to do more for the Union cause. Never at a loss for bold ideas, Lida soon came up with the concept of an underground newspaper for Union soldiers and promptly roped in sister Lizzie and friend Sarah Steer as fellow-editors. Thus was born, The Waterford News, quite possibly the only newspaper ever written by Union women to be published out of Confederate Virginia. What kind of women begin such a conspicuously dangerous work? Why, the kind bent on having their own way, of course — ones whose story you are about to learn. Lida (L) and Lizzie Dutton of Waterford, Virginia  Union Lieut. John William Hutchinson of the 13th New York Volunteer Cavalry Union Lieut. John William Hutchinson of the 13th New York Volunteer Cavalry When Barbara Black was a very little girl, her grandfather would sit her upon his knees and tell her the story, and, although she’d heard it a dozen times, she loved to hear it once more: [1] A handsome soldier in a Confederate uniform approached a pretty young miss for the purpose of asking her directions. His name was J. William Hutchinson, and he was actually with the 13th New York Cavalry, acting as a Scout in what he thought was enemy territory. The young lady was Lida Dutton, a Quakeress living in one of the only pro-Union villages in Lee’s Virginia. By his uniform, she assumed he was a Confederate soldier. By the fact she was standing in Virginia, he assumed she was a Rebel. He politely asked her the way to a certain place, and from there things took an interesting turn. Being a Quaker, Lida wouldn’t knowingly lie, but she also wouldn’t knowingly help a Confederate get where he was going any faster than he should, and so she cheerfully gave him directions using landmarks used only by the locals: “Left at Brown’s stump, right at Uncle Harmon’s well, left at Zilpha’s Rock...” As the end of the impossible-to-follow directions, Hutchinson quietly asked, “Miss, which side would you like for me to be on?” Momentarily flustered, she finally blurted out: “If you’re a Rebel, I hate you, but if you’re a Northerner, I love you!” At this point, he introduced himself and showed her his Union insignia. And that is how Lida Dutton met her match. In the first three years of the Civil War, Lida and Lizzie Dutton and Sarah Steer could be found caring for wounded Union soldiers,[2] hiding them from marauding Rebel troops,[3] and managing to hold together the farms and businesses their fathers and brothers had had to leave behind to avoid conscription into the Confederate ranks. But in the spring of 1864, they decided they would do more, and nothing — not the lack of goods nor the abundance of Confederate soldiers — was going to thwart their good efforts. At least eight issues of The Waterford News were published before the spring of 1865, and in each edition’s four, small pages these young women neatly packed a tidy meal of patriotic editorials, poetry, riddles, local news and humor, a sample of which reads as follows: "The next day or two the rebels again visited this district and appropriated to their own use several horses and two wagons loaded with corn, belonging of course to Union citizens. They also visited the tannery of Asa M. Bond and arrested thirty-five dollars worth of leather." WANTED A few stores... with Dry-Goods, Molasses Candy and other stationery, suited to the tastes of the community. Young and hand-some Clerks not objectionable.[4] The soldiers ate it up... to put it mildly. Not only did it boost the morale of the troops, it also brought in subscription fees – monies which the girls turned right around and sent back for soldiers’ aid.[5] The Waterford News was even perused by President Lincoln. Private Schooley of the 11th Rgt., Maryland Volunteers sent a letter to the President with this introduction, “To His Excellency Abraham Lincoln. Will your excellency please accept the two enclosed copies of ‘Waterford News’ and excuse me for taking the liberty of sending them to you... You will see by the Sending, the intention of the Fair Editresses in editing the Paper under the difficulties which they do. ‘Tis for to aid the ‘Sanitary Commission.’ They have already made up nearly 1000$ [sic] for the same purpose!”[6] To understand the nature of these exceptional young women, we must understand their social context: the history of Quakers (also known as “The Religious Society of Friends”) has been marked by unusual bravery and strength of character. Students of Quaker history find evidence of the persistent influence of a people of faith who helped change the course of American history, as well as evidence of America influencing the nature of Quakerism.[7] These competing influences are best exemplified in the history of Loudoun’s Quakers — a people who found themselves struggling to maintain a pacifist tradition in the midst of Civil War. By the early nineteenth-century, most Loudoun Quakers associated themselves with the Hicksite faction of the church which espoused a more liberal point of view than Orthodox Quakers. By the time of the Civil War, they were still pacifists, met twice weekly for Meetings, disciplined their members, and encouraged plain dress, but further assumptions are destined to break down.[8] They had been living in the middle of a heated political situation for several years, and their pacifism had been sorely tested. When John Brown’s Raid occurred so near to Loudoun, local militias were formed. Quakers were told to show up for muster or pay a fine. At the beginning of the war, the Confederate army took Quakers for laborers or jailed them for use as bargaining chips. As a result, most headed north, but several risked church discipline and joined the Union army. One of those men was young James Dutton, brother to Lida and Lizzie.[9] By 1862, Lizzie had fallen in love and become engaged to a Lieutenant Holmes of the 7th Indiana Regiment. The matter had become personal, such that when it came to a choice of allegiance between country or faith, Quaker women like Lida, Lizzie and Sarah stubbornly chose to support both. A Waterford News editorial boldly stated, “Christians make the best soldiers.”[10] At every turn, Loudoun Quaker women refused to be categorized. Regarding the tradition of Quaker “plain dress,” for example, there is this interesting notation in the very first edition: “Great distress is felt by the ladies of this vicinity at not being able to appear at meeting in new bonnets, dresses and wrappings, owing to the stringent blockade.”[11] These women were very well educated and strongly encouraged to express themselves. Only a few years before the war, Lida, Lizzie and Sarah had been active members of The Waterford Literary Society, writing essays whose topics ranged from a thoughtful, “What is There Left to Write About?” to a hilarious ode “On Chickens.” Essays were read aloud to the group, gently critiqued by the members present, and then recorded in a large bound book. Thankfully, the Society’s volumes survived the war and rest in the archives of The Thomas Balch Library of Leesburg, Virginia.[12] One of the anonymous notes in the Society Essays reads, “Take life as it is, a real matter-of-fact thing, and do it justice,” and it is easy to imagine the “Fair Editresses” of The Waterford News taking the sentiment to heart. Although the Literary Society provided a place for young ladies to sharpen their wits as well as their pencils, their excellent educations began at home. Several years before the war, Sarah Steer had been sent north to a Ladies Academy, and John and Emma Dutton had always encouraged their four daughters to exercise full use of their minds. In a letter written in 1864 to his youngest, Anna Ellen, John Dutton wrote, “I take great pride in my childrens’ writing. I want each to exert themselves in this particular branch of learning and now is the time whilst thy little fingers are limber... Make it a rule to study — to think — weigh thy thoughts well for thy self. Don’t conclude things are right just because the mass of the people say so.”[13] As a result of such parenting and the Quakers’ insistence on female education (all this despite 19th century ‘Woman as Shelf-Ornament’ thinking), Lida, Lizzie and Sarah’s writings are a treasure of womanly expression: The young ladies of Waterford, Loudon [sic] Co., Va., are hereby notified to meet the first opportunity and lend their mutual aid in filling a large mud-hole with stone, said mud-hole being located in the middle of Second Street... the men have driven around it so much that it is extending each side. Being fearful the gentlemen will get their feet muddy, the ladies will try and remedy it.[14] While the state of the Second Street mud-hole made itself useful as a running joke (c.f. opening quotation), the young women knew how to turn a joke on themselves, as well. The paper contained a marriage column, but it was always empty. At the bottom of the column, a sad little footnote would appear, such as, “Words are inadequate to express our feelings on this subject.” Edition number three contained this note of surrender: “We think there is no prospect of having this long-continued vacancy filled until after the war: so we will discontinue it for the present.”[15] And how did the soldiers react to the news? In a word: quickly. The very next edition reads, “After the marriage column was closed, the young gentlemen became very patriotic, volunteering to serve a lifetime, and proposals numerous flocked in. We will make them feel that delays are dangerous.” All humor aside, letters from Union soldiers which appear in the paper make it clear they had a serious appreciation for the young ladies’ efforts. And, make no mistake, it was an effort. With no paper and no money, getting a newspaper out of Confederate Virginia was no small task. Draft copies of The Waterford News had to be smuggled north across the Potomac River. The Baltimore American voluntarily printed the newspapers for them. Subscriptions were handled through the Federal Post Office at Point of Rocks, Maryland; the active Confederate troops made it impossible for the girls to distribute the paper from their homes. For their efforts, the young women risked severe “discipline” by the Confederate army, as did all of Waterford for its pro-Union sentiment. The worst Confederate attack on the villagers occurred in 1862: Confederate troops arrived to forage and announced when they were through they intended to burn the pro-Union village down. The wife of Samuel Means of Waterford ran to the only person she knew who still had a horse: a farmer who lived just outside of town. She asked him to ride to Union General Geary, stationed just a few miles away, and tell him to send Union troops to save the town. The fellow flat-out refused. She then asked him to lend her his horse so she could make the ride. Again he said “no.” She then said, “Then I will steal thy horse and go myself.” And so she did. General Geary promptly dispatched troops to the town, and Waterford was saved... for the time being.[16] With war literally at their doorstep, Lida, Lizzie and Sarah chose to publish the newspaper, despite personal risk, and even personal tragedy. The July 2, 1864 edition of The Waterford News encouraged its readers to press on: "Let not kind words, loving tones, and love of good deeds cease to find a place in our hearts. Now, if ever, is the time to ‘cast bread upon the waters,’ when tired and weary ones are all around us, and starvation stares so many in the face; when loved ones are struggling with pain, and joy and happiness are hidden in the distance; when hope leaves us and misery looks at us with hollow eyes. Let us be up and doing — old and young — we have no time to idle; every quickly flitting moment is to be improved, every space filled up." This editorial, which might be dismissed as nothing more than flowery patriotic sentiment, becomes poignantly descriptive when we discover it was written soon after Lizzie received the news her fiancé, Lieutenant Holmes, had been killed in action. Doing life justice means that much more when life isn’t doing you justice in return. In late November of 1864, General Grant authorized a raid on Loudoun County. It has become known as “The Burning Raid,” but The Waterford News called it “The Fury Order in Loudoun.” Frustrated with the seemingly unchecked activities of Colonel Mosby’s Rangers, Grant’s concept was to burn out the farms still able to provide forage to Mosby and his men, and to this end a multitude of barns were burned and livestock was killed or driven off. In addition, men under 51 capable of bearing arms and any slaves remaining in the area were to be taken. At this point, political sentiment was unimportant. Mosby gathered forage from whoever had goods, thus the Union army visited whoever had goods. So, in a sad twist of fate, Pro-Union Loudouners had the unpleasant task of watching the Union army destroy in less than a week what they’d been protecting from bushwhackers and Confederates for four years. Between November 27th and December 2 of 1864, the skies over western Loudoun were dark with the smoke of hundreds upon hundreds of fires.[17] And, again, Loudoun’s Quaker women persevered. Major J.B. Wheeler of the 6th New York recorded that, “At Waterford, Loudoun County, Virginia, two young ladies perched on the wide gate posts in front of their home, waving American flags and said as their hay was being destroyed, ‘Burn away, burn away, if it will keep Mosby from coming here.’ ” Tradition holds that one of those young women was Lida Dutton.[18] An editorial in the Jan. 28, 1865 edition of The Waterford News had this to say about the ‘Fury Order:’ We do not believe, if our Government had been as well acquainted with us as we are with ourselves, the order for the recent burning would be have been issued; but having suffered so much at the hands of the Rebels ever since the commencement of this cruel war, we will cheerfully submit to what we feel assured our Government thought a military necessity. It should be noted not everyone reacted as stoically. When Union soldiers demanded matches from Quakeress Ruth Hannah Smith for the sole purpose of using them to burn down her barn, she quietly held the lucifers in the steam from her teakettle before handing them over. Her barn was saved.[19] We know that the effects of war did not alter Lida, Lizzie and Sarah’s resolve, so it should come as no surprise that when peace came they continued to “do life justice.” Sarah Steer applied to the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Philadelphia Meeting and to local Quakers for the funds to open a school for the children of freedmen.[20] The school was built in 1867, the first of five in the County, but Sarah didn’t wait for the walls to go up around her. She began teaching in 1865 and so became the “first teacher of black children” in Loudoun County.[21] The building, an historic property now known as “The Second Street School,” is owned by The Waterford Foundation and is the site of a unique living history program. As part of the Loudoun County’s Third and Fourth grade curriculums, children are able to spend a morning in the one room school house taking on the identities and responsibilities of the African-American children who attended in 1880.  The Second Street School, the first school for freed black children in Loudoun County, Virginia, was founded by Sarah Steer The Second Street School, the first school for freed black children in Loudoun County, Virginia, was founded by Sarah Steer An excellent summation of the trials and tribulations of Waterford Quakers is beautifully detailed in the Waterford Foundation book, To Talk is Treason, by John Souders, Bronwen Souders and John Divine. Most of the story of Lida and Lizzie Dutton and Sarah Steer is contained therein. It is abundantly clear from their histories, each of these women were capable of being that Editor referred to as “bent on having her own way.” And what of Lizzie and Lida Dutton after the war? Both continued to write, submitting poetry and articles to local newspapers on occasion, but life still had a few surprises left for them. Lizzie continued to live in the now quiet village of Waterford, and we could forgive her for assuming the exciting portion of her life was over. There had been one fleeting correspondence between herself and a Lieut. James Dunlop of the 7th Indiana - a friend to her fallen fiancé and the very man who’d written her with news of his death - but, after the war, Lieut. Dunlop had gone home to Indiana to marry his childhood sweetheart. But fate decreed Dunlop’s wife would die within two years of the marriage. He never remarried, and for years he let the thought nag him: “Whatever happened to Lizzie Dutton?” In 1881, he came to Washington on business and used the excuse to send a card to the Dutton home. The reply was a letter from Miss Elizabeth Dutton. He took himself straightway to Waterford. An account of the event reads, as the two renewed their acquaintance, “matters flowed on so easily, smoothly, and naturally, that in a few weeks Mr. Dunlop found himself at his Indiana home busily engaged in preparing for the reception of a new mistress, and soon the little town of Waterford was all a blaze of light and a scene of general rejoicing, for the lady was popular and beloved by all.” Joseph Dunlop and Lizzie Dutton were married January 22, 1882.[21] Last, but not in the least least, there was the matter of strong-minded Lida. Was she be able to square things with her Union Lieutenant after her bold attempt to hood-wink him? Yes, but not before he winked right back. Lieutenant Hutchinson followed his surprise introduction by telling Lida he planned to hold her to her bold promise — her promise to love him if he were a Northerner. When she regained her composure, she told him she believed she’d said “like,” not “love.” He strongly disagreed and promised to return for her after the war. Well, like him or love him, when Lieut. Hutchinson came back for her, she married him. Apparently they continued the happy argument of “like” vs. “love” with their children as audience... their grandchildren... and, eventually, their great-grandchildren. The two were man and wife for 53 years before William passed away. [23] Heroes are the simple creation of continually choosing to do life justice in the midst of trying circumstances. Thanks to the preservation of Loudoun history, we’re able to celebrate the heart of these three heroes: Sarah, Lizzie and Lida... three women editors who were, thank heaven, absolutely bent on having their own way. And they must have the last word: Many threats have been made about burning our houses over our devoted heads, but Waterford is still standing. And we trust it may stand long in the future to remind other generations that in its time-honored walls once dwelt as true lovers of their country as ever breathed the breath of life-long-suffering but faithful... to the end." - The Waterford News, July 1864 This article was first published in Citizen's Companion Magazine The author, Meredith Bean McMath is an award-winning historian and prize-winning playwright who resides in Loudoun County, Va. Her Civil War novel, Pella's Angel, is set in Loudoun County, Virginia during the Civil War and is available on Amazon and via Kindle.com REFERENCES [1] Letter of Barbara Dutton Conrow Black to Ladies Home Journal dated Feb. 4, 1962 (copy in Waterford Foundation Archives, Waterford, VA) [2] Waterford Perspectives, Education Committee of The Waterford Foundation, Waterford Foundation Archives [3] To Talk is Treason, Bronwen and John Souders and John Divine, The Waterford Foundation, Waterford, VA (1997) p. 56 [4] The Waterford News, Vol. 1, No.’s 1-8 (copies in “Civil War File” of The Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA and The Waterford Foundation Archives) [5] ibid, Vol. I, No. 2 (Nov. 6, 1864) [6] “Robert Todd Lincoln” papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (referred to in Oct. 6, 1955 article from The Blue Ridge Herald, “Lincoln Papers Reveal Waterford Had Newspaper During Civil War;” copy in “Civil War File,” Thomas Balch Library). [7] To Talk is Treason, et al [8] The Transformation of American Quakerism, by Thomas D. Hamm, Indiana Univ. Press (1988), p. 52 [9] “Girls Published Civil War Newspaper,” by Emma H. Conrow, Baltimore American, February 5 1922, p. C-3 (copy in “Civil War File” at the Thomas Balch Library and The Waterford Foundation archives). [10] The Waterford News, Vol. I, No. 6 (Nov. 26, 1864) [11] ibid, Vol. I, No.1 (May 28, 1864) [12] Essays of Friends Literary Society, Waterford, 1857-60, Rare Manuscripts — Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA [13] To Talk is Treason, p. 87 [14] The Waterford News, Vol. I, No. 1 (May 28, 1864) [15] The Waterford News, Vol. I, No. 3 (July 2, 1864) [16] Waterford Perspectives [17] Hillsboro: Memories of a Mill Town, Hillsboro Bicentennial History Ctte, Pub’d by the Hillsboro Community Association, p. 25 (The Thomas Balch Library) [18] To Talk is Treason, p. 92 [19] Ye Meetg Hous Smal, Werner and Asa Moore Janney published by Werner and Asa Moore Janney (The Thomas Balch Library) p. 42 - insert [20] Friends Intelligencer, vol. XX, pp 250-251 (copies in Waterford Foundation Archives) [21] The County of Loudoun, by Nan Donnelly-Shay and Griffin Shay, The Donning Co. (1988) p. 53 [22] Camp & Field, Sketches of Army Life, by Wilbur F. Hinman (Cleveland, 1892) (Ref., The Thomas Balch Library) pp 422-423 [23] “Commonplace Book” by Mary Frances Dutton Steer (collection of letters and memoirs), Waterford Foundation Archives, p. 15

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |