|

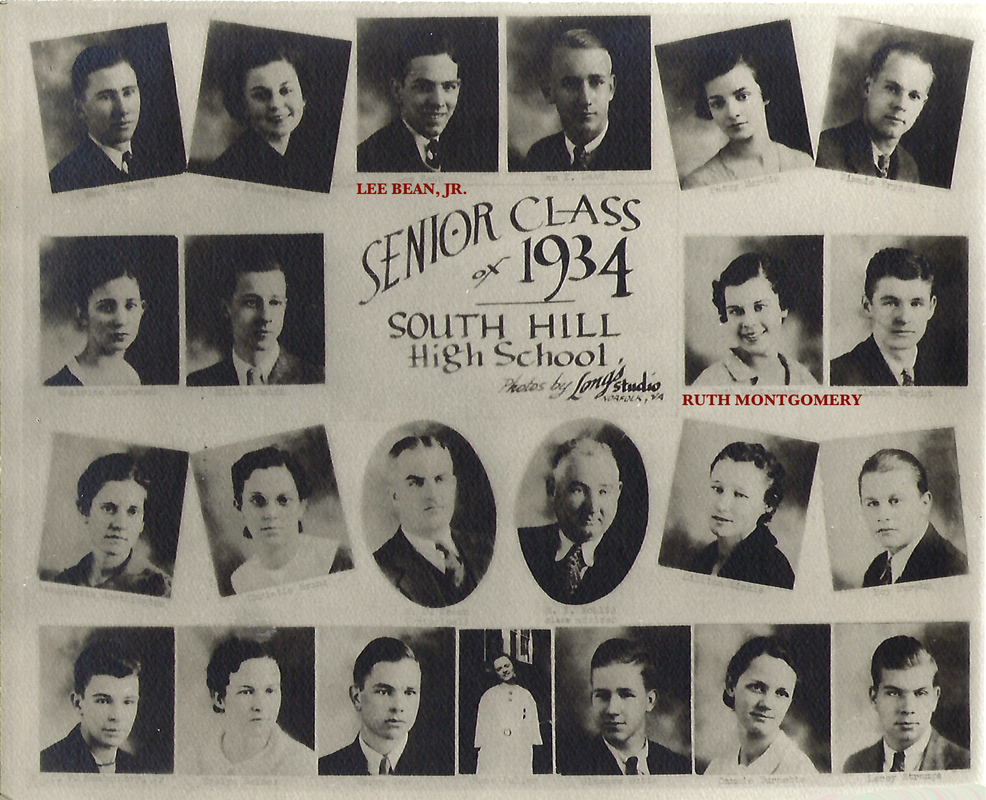

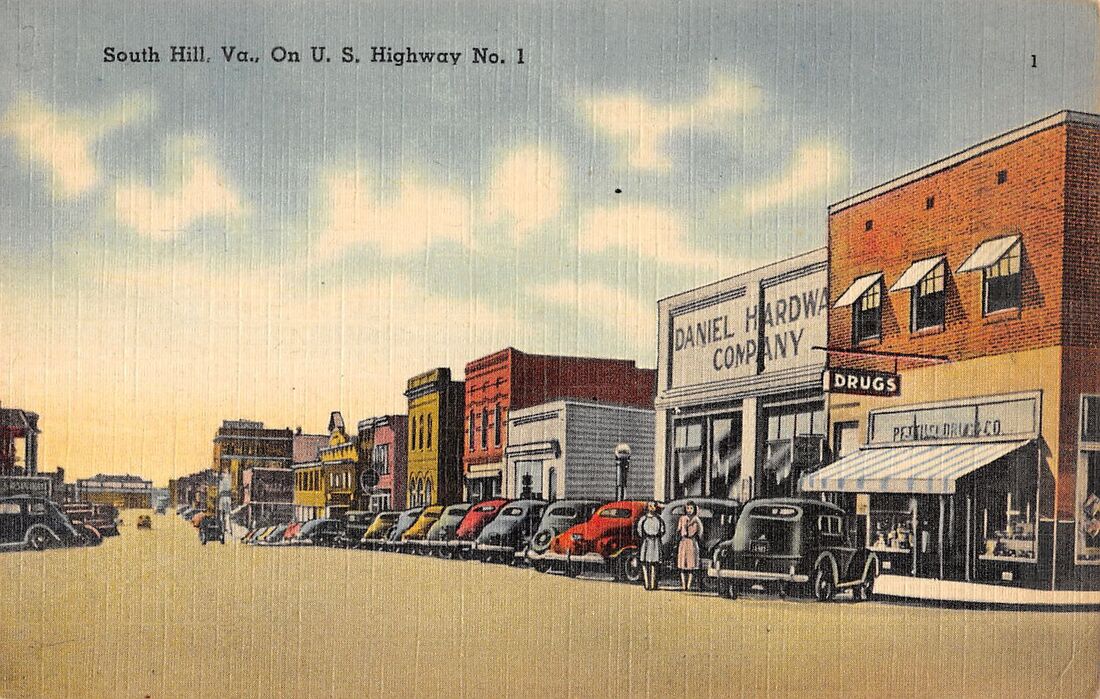

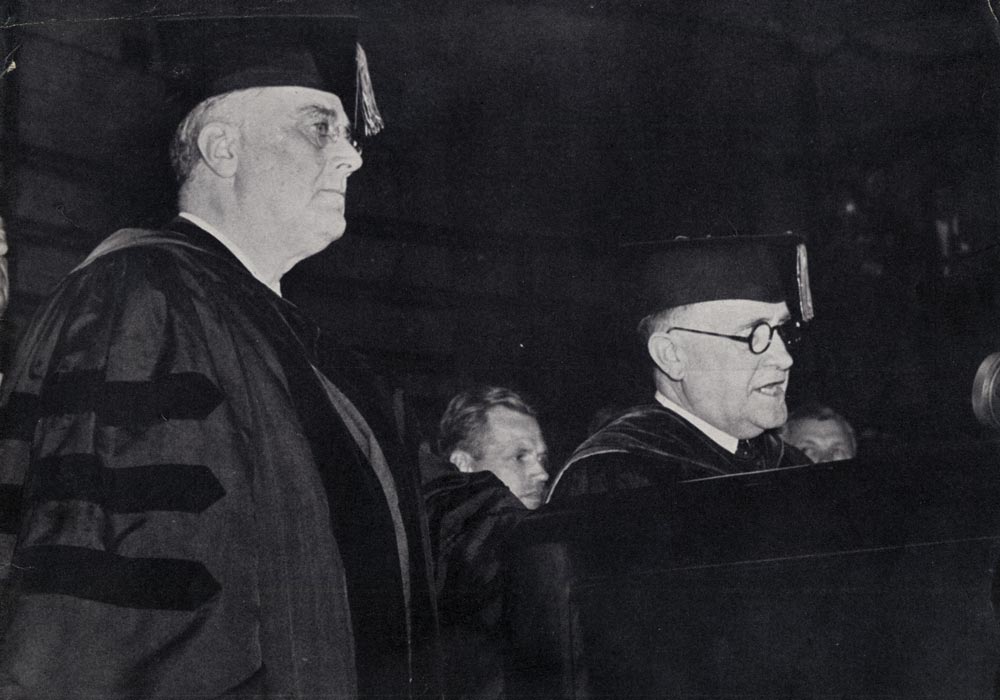

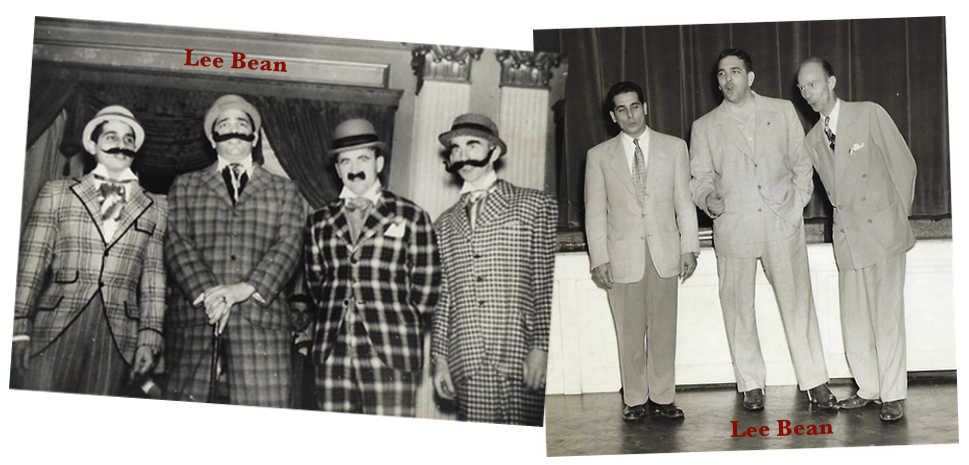

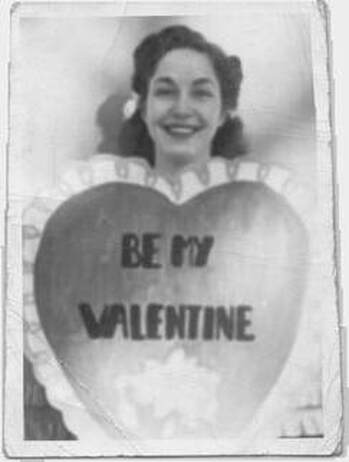

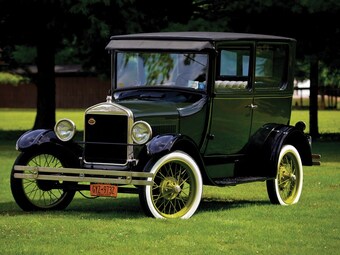

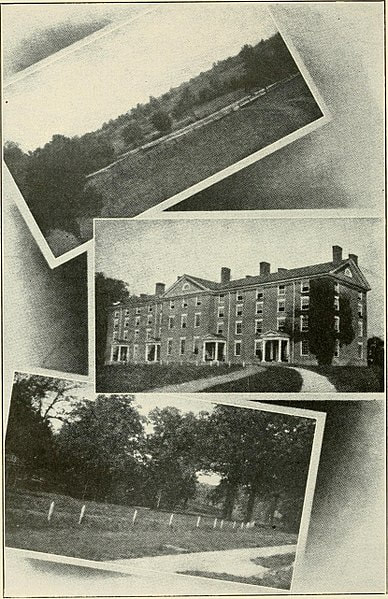

Lorenzo Lee Bean, Jr. was The son of a man who had grown up in the hills of West Virginia, and learned how to take care of himself. And he was determined to teach his son the same skills. Hi son had an excellent sense of humor and the dark eyes and complexion typical of the Welsh. But with a name like Lorenzo, he was sometimes taken for an Italian child and had two bossy older sisters, so that sense of humor came in handy. Nevertheless, he changed his name to "Lee" as soon as he could. Lee's first memory came at the end of World War I. His father, L.L., had served in the home guard, and when the boys came home from "Over There," the whole town came out to greet them. Lee remembered standing on the butt of his father's rifle as his father steadied him, so he could see the World War I veterans marching through Fort Meade, Florida - a sight that left a deep impression on the toddler. His next memory was a little less fun. Their back yard held a huge tree dripping with the Spanish Moss indigenous to the region — the bane of mothers who liked to keep their children tidy - one day the three little Bean sprouts were headed to a birthday party in crisp, clean whites: Lee wore linen shorts and shirt, and his sisters had lovely dresses of fine lawn and cotton. As Lee walked down the sidewalk, he decided to pass through a slick of Spanish Moss. He didn't make it and went down on his backside, covering his fine outfit with green slime. He sat there in the slick moss and began to cry, while his sister Virginia laughed and laughed. Then Libba walked up. She'd missed the show, so Virginia decided to demonstrate Lee's hilarious fall - and wound up on her backside beside him. They cried in stereo. Such is the sad tale of the white birthday outfits. Adelaide loved her family well, but she was an over-protective mother with a penchant- perhaps you could call it an obsession - for tidiness. This put a strain on free-spirited little Lee, and around the age of eight, he developed colitis. A doctor and family friend recommended he be sent to a quiet, farm environment during the summer. Probably made excellent sense to his father, L.L., had been well-raised on a farm. Lee spent two summers there, and, sure enough, these "visits" cleared him of his troubles; he loved farms ever since. His father took Lee hunting now and then, always instructing Lee on the finer points of good sportsmanship. For instance, Lee was never to aim at a bird on the ground who was capable of flight. It was contrary to sportsman’s ethics, because you weren’t giving the bird a fighting chance. Another equally good reason is that if you aimed low, you could strike a human. One day the two were out dove-hunting, and they'd walked away from each other for a bit. Lee heard a welcome cooing sound, quietly stepped up behind a palmetto bush and looked over to see a dove in a clearing. He thought on his father's words and prepared to flush the bird out when something caught his eye on the other side of the clearing. There stood his father, L.L., behind another bush, his gun pointed down at the dove. Lee had just enough time to hit the deck before he took the shot. Then Lee stood up, unharmed, and stared at his father who proceeded to turn white as a ghost. They two walked home in utter silence - the incident weighing heavily between them. Father and son would also go on long camping trips to hunt with friends. One would cook for all, and the rule was this: whoever complained about the food had to cook. One night, a fellow decided to try to get L.L.'s goat by pouring salt into his coffee when he wasn't looking. L.L. took a big gulp and spewed the contents all over the campfire as he bellowed, "SOMEbody put SALT in my coffee!" Everyone held their breath as the cook looked up in anticipation. L.L. quickly added, "But it sure is good, though!" L.L. was a man of pride. To a fault, you might say. The man never said he was sorry. An example of his unnerving obstinacy can be found in the family's regular Sunday Drive. Back then, folks would pile into their Model T Ford's and just drive about the bumpy roads and enjoy the shaky view as best they could; at some point they'd stop and have a picnic, and then they'd pile in the car and trundle back home. L.L. always got lost.  Adelaide would inevitably point this out, and she would always hear the same answer: "Adelaide, we are not lost! I know exactly where we are: we are in the great state of Virginia!" and that's where the discussion would end. In 1920, the Beans received notice that L.L.'s father, David, had passed away. His obituary described David Ferguson Bean as 77 years of age, "a man of unassuming manner and friendly to everybody, and very close to his friends of whom there were many. He was a man of great tenderness of heart and was generous to the poor. He held the respect of all who knew him and his acquaintance was large." His services were given at Asbury Lutheran in Moorefield, West Virginia, and he was interred alongside his wife in the family plot behind the George Bean house on Simon Bean Mountain. It is said L.L. only returned to West Virginia a couple times in his lifetime, as his childhood away from the farm had not been as pleasant as his father's. But attending his father's funeral was one such visit. L.L. was tight-lipped on the reasons for staying away, but he was happy to relate the more pleasant stories of his youth. Knowing L.L. from the letters he left behind, it was likely one reason was his father's profession: growing apples and turning them into fine Apple Jack (a friend to all, indeed). In 1924, L.L. moved the family to Lakeland, Florida to get into the Real Estate and Insurance business. Then came the Great Depression. Sales and banking died, as did the remains of L.L.'s business hopes. As so many did, they headed home for comfort. They were soon Virginia bound, but it was to South Hill, Virginia, where Adelaide's relations lived. In 1932, L.L. took a job as a Bookkeeper at the South Hill Grocery Company. Lee, a teenager, now, liked South Hill very much, and South Hill liked him. A natural athlete, he spent every waking minute playing baseball or football.  Hampden Sydney College Hampden Sydney College The mountain men of the Bean family have a tendency toward height, and Lee had the family growth spurt in high school, where he rose to a thin and wiry 6'1". Right around that time, he developed a hard crush on a pretty young girl in his class named Ruth Montgomery. Ruth had the look of a 1930s Beauty Queen: a round, pert face, short, wavy hair and big, beautiful eyes. She invited Lee to her birthday party, and he was very pleased to accept the invitation. But he had a friend coming up from Florida that weekend. "Could my friend come as well?" "Oh, yes!" Then Lee had a devilish thought. "Oh, that's swell, but there's just one thing you need to know about Fred. He's a bit deaf. So, if you could speak up when you meet him, I'd be grateful. Then he wouldn't have to be embarrassed about it." "Oh, all right! I'll remember that." Lee greeted his friend at the train station and told him about the party. When they came to Ruth's porch, Lee paused. "Now, Fred, Ruth's a fine girl, but there's just one thing you ought to know about her..." and on he went. Lee knocked, and when pretty Ruth came to the door, he exclaimed very loudly, "RUTH? This is FRED McDONALD, FRED? This is RUTH MONTGOMERY!" and then he backed away from both of them. Ruth and Fred began to yell salutations back and forth, until Ruth became so flustered, she yelled, "Well, there's NO NEED TO YELL AT ME! I'M NOT DEAF!" Fred shouted back, "We'll, I'M NOT DEAF, EITHER!" At this point both turned to look at Lee, who was about to fall off the porch laughing. Ruth didn't speak to Lee for days. In 1933, Lee entered Hampden-Sydney College, an all women University in Hampden Sydney, Virginia. The school was a perfect fit for this athletic young man. He joined the Hampden-Sydney Tigers football team, led by a quarterback named Homer Hatten from West Virginia, and Lee and Homer, whose nickname was "Moose," became fast friends. Lee also joined Chi Phi Fraternity and made another set of lifelong friends. And, in his spare time, he honed his Prankster Skills among equally clever devotees of the art. Fall at Hampden-Sydney began with a ritual: when the apples were ripe, the bravest boys ran to a nearby apple orchard, climbed the trees and ate their fill... all night long. The trip was a hoot for the boys but an annual disaster for the apple orchard owner - who happened to be a professor at the college. And that year was the year he decided he was going to fix things. When the apples were just about ready, he went to his orchard and laid in wait for the thieves, his trusty shotgun and a pile of little paper pellets by his side. If you load a shotgun by replacing the lead in the shotgun shells with balled up paper pellets, you will get a satisfying kaboom and a flash of something akin to a fireball. Terrifying to behold. Each night he loaded up the weapon and waited. The third night, they came... Lee Bean among the hopeful apple wranglers. They whispered as they walked, watching for the Professor. They crawled over his fence. He waited. They carefully chose their trees and climbed. He waited. A sentry was posted at the gate, turning his head side to side to watch the night. The rest began to ate fruit, and soon began to chat with one another tree to tree. They started laughing and singing and throwing apples at one another. Still he waited. Waited until he was sure they were perfectly, perfectly relaxed. Waited for the sentry to turn his head away from him one more time. And then he rose up from his hiding place and watched the sentry turn back and catch a glimpse as he yelled out, "I GOTCH'OU NOW!" Ka-bloom went the shotgun. And as he reloaded, he listened. They yelled in fright and fell from the branches in terror. "YOU AIN'T GONNA' GET OUT'A HERE ALIVE, I TELL YA'" Ka-bloom. The boys screamed as they ran, holding their busted arms, stumbling over the fences as they made their escape. One more "ka-bloom" toward their frantic retreat, and the work was done. Downed branches lay all over the orchard. His apple crop was destroyed. Yet he was a happy man. There was only one thing left to be done. The next morning, he walked the paths of Hampden-Sydney, and every time he met a young man with a black eye, a bandaged head, a limp, or an arm in a sling, he took off his hat and greeted him with, "Good morning, Mister Black. How d'you do, Mr. Evans. Fine morning, Mr. Bean..." and extended the same kindness to the wounded students who sheepishly appeared in his classroom. From then on, the professor's apple crop was left unmolested. But Lee Bean's taste for adventure wasn't undone. It was simply going to find new, er, "pastures" to explore. One night, Lee and his best friend and room-mate Bobby Richardson decided they wanted some ice cream. They knew just where to get it. The Dean of the School was holding a Faculty Ice Cream Social. The freezer was in a second story room of the Dean's home, and the kitchen had an open window - right next to a sturdy drain pipe. That ice cream was practically begging to be snatched. The boys took off their shoes, rolled up their pants and shimmied up the pipe, crawled inside and crept toward the freezer. The goal almost reached, they could almost taste the creamy home-churned confection - when the Dean's wife stepped into the kitchen. "Oh!" she cried, but quickly recovered. With her best Virginia manner, she drawled, "Mr. Bean! Mr. Richardson! What a pleasure to have you drop in. You simply must come greet everyone." "Oh, no, ma'am, we couldn't." "Ou-our feet! No shoes!' "Oh, that doesn't matter at'all. Ahh know they'll just love to see you!" A more perfect punishment could not have been devised. Shoe-less, pant legs rolled, their intent obvious to all, the boys had to walk in to that party and be formally introduced to each of their teachers and all the important persons present, in turn. Next, she had them sit upon her delicate antique chairs and eat ice cream from her fanciest dishes. With a final flourish of hospitality, the Dean's wife sent them off through the front door. Obviously Lee Bean needed his ethics readjusted. For that, there was compulsory Religion Class. Religion was taught by one Professor McGee, known among the students as "Ole' Snapper", due to his striking likeness to the sound, look, and sudden fury of that venerable form of turtle. Snapper's classroom was in an upper story, turret-like room (no doubt chosen for its proximity to heaven), with a winding staircase much like an old castle keep. As you'd expect, Snapper was a punctilious man who never missed a class - unless it snowed. A rarity in southern Virginia, any amount of snow stilled all campus activity. You only had to go if your Professor made it to class, and Snapper was too old to manage snow. One winter morning the students awoke and rejoiced to see to see Mother Nature had blessed the campus with a thick, white blanket of frozen freedom. So certain they had the morning off, they lounged about the dormitory in their pajamas... until a young man glanced out the window at about two minutes to 8 a.m.. "SNAPPER!?!" His comrades rushed the windows. Yes. Ole' Snapper was headed for the turret. It was a miracle. He was walking on top of that deep snow as though he was walking on water. As he got closer to the dormitory, the miracle took shape: two humongous snowshoes - Canadian tennis rackets - strapped to Snapper's sure and steady feet. Ole' Snapper was smiling as he walked. The boys were late, but they came. Snapper looked about, grinning foolishly; he knew he'd caught them all. They stood at their desks, waiting to be seated still wearing their winter coats (mere pajamas don't provide much protection in a drafty, cold turret in the dead of winter). Snapper smiled all the more at their unusual attire, and then he bade them sit and begin. Come spring, Snapper's boys planned their revenge. Most of the young men had grown up on farms, so they knew something about cows: like the odd fact that a cow is willing to go up a stairwell, but she won't come back down without a... "fuss". The cow had never trod such boards, she'd never seen a turret, and she was very unhappy. In fact, she made known her deep unhappiness all over the classroom. As the boys stood at their desks before class, they were a little unhappy themselves. This particular stunt had, uh... backfired, so to speak. But they began to enjoy themselves again as they heard Snapper's plodding step upon the stair. Snapper entered the room, observed the cow mooing forlornly in the corner, and walked up to his desk without a word. The students' faces fell. Snapper's desk stood on a raised platform, and no one thought to walk the cow up on to Snapper's platform. The Professor's portion of the room was smelly - but otherwise pristine. Sadly, this could not be said of several of the boy's seats. Naturally Snapper looked about the room and told everyone to be seated. And therein "lay" their punishment. Those who could sit, did. Those who could partially sit, partially sat. Those who couldn't sit, stood beside their desks the entire class - one hand taking notes, the other holding their noses. After Snapper gave his lesson and left the turret, the students went to a great deal of trouble to arrange to have the cow taken out a window. You'd think after these disasters the students would have learned to leave pranking alone. But, no. There was a farmer who had a strawberry field. Come May, Lee and his friends decided to raid the strawberry patch. The farmer was ready for them. When they'd filled their hats to the brim with fresh strawberries, the farmer stunned them by stepping out from behind a tree. He carried an elaborate tray, which he raised as he spoke these words: "Them strawberries taste much better with cream and sugar, boys." Seems all the clever men of Lee's youth were farmers. Conversely, all the fools were those who called themselves important. Lee never talked down to people, and he never bowed and scraped to those made it a habit to overestimate their self worth. Down in Florida there'd been a boy who'd been named after six rich uncles in order to inherit from them upon their death. Yukson Haben Obergat Teban Earnest Fleming Cox thought he was King of the Hill. And he was the meanest boy in town. They called him 'Yuk' for short. The kids used to come to his front yard, form a circle and chant his name until he came bolting out of the house, hoping to catch one and beat them senseless. Sure enough, by high school, Yuk had inherited from two of the uncles. Then he became the meanest and the richest boy in town. No friends, no respect, lots of money: To Lee's mind, useless. Conversely, in South Hill, Virginia, a truck drove through town with a full load and got stuck under the town's overpass. Everyone came out to try to try to fix the problem. Police, firemen, town council - all the "important" people, and the neighborhood, too. Dismantle the cargo from the back, take apart the truck - you name it, they thought of it. Along came the town drunk. He surveyed the situation from his slanted point of view and blurted out, "Why don'chou let the air out o'them tires!" No friends, no respect, no money - just incredibly useful. Well, there was a particular snob at Hampden-Sydney who got on everyone's nerves. He was easy to pick out, because he was the only student who'd brought a car - his own car, as he readily pointed out - to school. A brand spanking new Model-T Ford. One weekend, this young man went to visit relations quite a distance away. In light of the Model T's thin tires and the rough roads, he wisely decided take the train. As soon as the whistle blew on his departure, the students went to work. Those boys might not have owned their own Model-T's, but they sure knew how to take 'em a part and put 'em back together Mr. Ford had made it a point of pride to design the Model T in such a way that anyone could learn how to manage and fix the car themselves - and many did. When the fellow returned Sunday afternoon, he looked for his car and screamed bloody murder. "Who stole it!", he demanded. "Nobody", came the calm reply. "There it is", and a finger pointed skyward. He looked up to find his gleaming Ford - perfectly rebuilt - straddling the high ridge pole of a three-story dormitory. As mentioned, cars were a rarity, so the train was an important part of students' lives. If a boy couldn't get a date at nearby Longwood College (girls only), he'd arrange for a an old girlfriend to come in by train. One friend of Lee's, a dashing cavalier, invited a girl to come in for the weekend, only to realize he'd double-booked himself. He had a Longwood Gal set for the weekend's events, as well. He begged Lee to help him. Lee didn't care for the arrangements, but he did his duty by his friend. Lee met Train Gal and took her around campus while his friend shared a soda with Longwood Gal, etc., etc. Lee thought up a great excuse for the boy while he escorted Train Girl to the school dance in his friend's place (while he was dancing elsewhere with Longwood Girl). The weekend went off without a hitch; Lee sent Train Gal off at the station Sunday afternoon and sighed relief. And then Don Juan made just one mistake. He wrote thank you notes to both young women and slipped Train Gal's's letter into Longwood's envelope, and vice versa. He saw nor heard from either woman again. Ah, Longwood. A short walk for the fellows on a Friday night. If you didn't already have a date lined up, you could always take your chances at Longwood. Fellows lined up outside the girls' dorm, and the lassies came to the windows. Now the lights would be on inside their rooms, so all the fellows could see was the girls' silhouettes. You had to chat up and make arrangements for the evening with a silhouette. Eventually the silhouette would come down, and you'd find out whether you'd guessed right. Some silhouettes could look so promising in that second story window. It was like playing the lottery every Friday night... or Russian Roulette. But the best story of all to come from Lee's Hampden-Sydney was the Bell Puller tale. Ah, the morning bell. 6 a.m. every day, without fail. A huge, fifty-gallon bell sat high atop a twenty foot stand (so the sound could reach every sleepy ear). One long rope came all the way to the ground. One man, The Bell Ringer, came each day at five minutes to 6. Everyday he watched the second hand on his wrist watch until the time came. And he would pull. And the students would groan and get up, up, up. Then a student hatched a brilliant plan. One night all the young men went out into the dark and used ladders to hoist themselves up that tall bell tower. They tipped the bell upside down and used wooden boards to loosely hold it in place. Then they formed a bucket line from the creek and filled the bell to the brim with cold, fresh creek water. The next morning, the boys set their alarm clocks for 5:50 a.m. Everyone got up to wait by a window. The Bell Ringer came at five minutes to six. He stood at the base of the bell and looked at his watch. The boys waited in appreciative silence. And then, at six precisely, he pulled the rope and a dorm full of boys watched a grown man scream as 50 gallons of cold water hit his head and wash him to the ground. And the boys hung out their windows and laughed and laughed The Bell Puller was furious - so furious he stomped to the Dean of the School and demanded the guilty parties be expelled. The boys from the dorm were lined up outside for hours and hours as the Dean waited for the guilty youth who planned the assault to step forward. But not one of them ever did. Since the Dean couldn't send them all home, the matter ended right there. And the boys had one brief shining moment of triumph. They’d beaten the daylights out of that 6 o'clock wake up call. A lot going on that freshman year, and Lee looked forward to the next adventures when he headed home that summer. Back in his home town of South Hill, Virginia, he and Ruth became an item, so summer wasn't looking too bad after all. And in order to be his physical best for football the coming year, he thought he ought to take a physically demanding job. He began work at his Uncle Sam Dortch's Ice House. He worked hard and came and went from a freezing building into 90-100 degree heat each and every day. But one morning he woke up to searing pain shooting through his arms and legs. He couldn't move. Lee had contracted polio. Work at the ice house - the work meant to keep him strong - had actually lowered his resistance. There were only two cases of polio in South Hill that year: Lee and the other young man who'd worked there with him. Years later, he told his youngest daughter that the pain he felt those first three months was so excruciating, if he could have found a means to kill himself, he would have. As he lay there, he fell into a deep depression. A young man with great prospects was trying to face the loss of every happy expectation - no more football, no more pranks - even Ruth quietly pulled away from him. What was there to live for? But his friends and family rallied around him. Particularly his father, L.L.. Lee's self-pity may have been understandable, but it did not sit well with a mountain man like L.L. Bean. From the very beginning, his father's words were unremittingly harsh: Get over it, get up, get on with life. Quit feeling sorry for yourself; get up and DO something! The words struck Lee as nothing less than cruel... but they were exactly what he needed to hear. Lee used humor to get the most out of life until then, but now it was his father’s encouragement - his call to Lee to have an iron will - that would take him through the rest of it. and along with his father's rough exhortations, were the daily visits of his mother. Adelaide now used her over-protectiveness to help Lee make a new life. The doctor said there was a small chance Lee could regain the use of his arms and legs, but it would take daily movement - painful daily movement - then long sessions of exercise. Adelaide was up for the task, even if Lee wasn't. She came to his room every day to massage the failing muscles and help Lee push himself to his limits. The exercises were hideously painful, and, for his legs, the efforts turned out to futile. But the hard work on his arms paid off. Over the course of two-years, his arm muscle returned, and he learned to walk on crutches - Canadian Canes, they called them at the time. His legs - which grew thin to the point of skin over bone and nothing more - were fitted with strong metal braces, and he used his old physical agility to learn to move with quick grace on metal legs. And all during that difficult two-year rehabilitation period, he kept up with his studies - ever hoping to graduate along with his friends at Hampden Sydney. And, amazingly, he made it and was allowed to join his senior class at the College. But, although he could get around quickly on crutches and braces, there was no "handicapped access" anything back then, so certain classrooms were seemingly out of bounds. That's when a good old friend from the football team, Homer Hatten of West Virginia, provided a solution. "Moose," offered to pick Lee up before class - literally - and take him around. He would throw Lee over one shoulder and ran him to class, and that's how Lee Bean, Jr. completed his education at Hampden Sydney. He was graduated in 1937 alongside the classmates he'd begun school with four years before. By that time he'd decided to become a lawyer. There are a large contingent of Bean cousins practicing law back in Hardy County, West Virginia, so it could have been DNA at work. In any case, he was accepted to The University of Virginia Law School and began in 1937. But he needed extra cash in order to assist with tuition. Enter the New Deal. Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration created millions of new jobs, and Lee Bean was one of the lucky recipients. He became an assistant to Dean Ribble, Dean of the Law School. One afternoon late in his second year he was standing at the counter collating when he overheard the Dean's voice rising from inside his office: "I am TELLING you, you cannot FAIL the SON of the President of the UNITED STATES!" Turns out, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Junior was a law student at UVA but not a good one. As Lee stood there, mouth ajar, the door swooshed open and the Dean's head appeared. "Bean?" "Yes, sir?!" "What's your average in Contract Law?" "96." "Get in here." Yes, Lee wound up tutoring F.D.R., Junior, so he could pass Contract Law and graduate that year. His not being able to graduate would be embarrassing, yes, but even more embarrassing when the President of the United States was coming to the College to give the University of Virginia Law School Commencement Speech. And tutoring this young man was no easy task Turns out, F.D.R., Junior had two baaaaaad habits: women and drink. And, as a result, Lee lost a lot of hair. Every week Lee struggled to help Junior understand Contract Law, and every weekend Junior would disappear to enjoy various and sundry vices. Then every Monday, Lee was there to try to pick up the pieces and start again. But. by golly, F.D.R., Jr. passed Contract Law and was set to graduate along with Lee in June of 1940. And when Junior's father, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, came to give the Commencement address, he wanted to thank Lee personally. So, on June 10th, Lee was told to be at a certain place on campus at a certain time, and when the time came, a large limousine rode up. The chauffeur came to the back door, opened it and asked Lee to get in. He did. And there was the President, sitting beside him. What Lee was thinking, one can only imagine. Knowing the President also suffered from polio had to be a huge inspiration. As L.L. would say, Nothing should hold a man back, and here he was two feet from the truth of that notion. He sat in that limousine, and the President thanked him, and then he asked Lee if had any hobbies. "Yes, sir. Philately." Lee had collected stamps since he was a boy. "Ah! Well, I'll send some stamps around, then." Lee left the limousine, beaming. F.D.R. went on to provide the speech to the law school graduates. The war news was grim that day: Italian troops had just invaded southern France, and so President Roosevelt put a message in his address. He described Mussolini's invasion as a "stab in the back," and so that speech went down in history (Further information: https://uvamagazine.org/articles/the_hand_that_held_the_dagger/ ). According to the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, F.D.R., Junior went on to be "admitted to the bar in 1942, called... to active duty as an ensign in the U.S. Navy and served in North Africa, Europe, and the Pacific... [was] awarded the Purple Heart Medal and the Silver Star... vice president of pres. Truman's Committee on Civil Rights in 1947 and 1948," served in congress, etc., etc. You'd have to say things turned out all right for him. As for the President's promise of stamps, Lee never really expected such an important man to bother with details. So he was shocked when three months later a huge plastic bag arrived - two-foot by two-foot - stuffed full of stamps from all over the world. With it was a letter from the Post Master General Farley of the United States, stating the President had personally wanted to thank Lee with this gift of stamps. Upon Lee's graduation, he took a job with the government, but he always regretted being unable to serve his country during World War II. His friends were becoming Air Force Fighter Pilots, and that would have been Lee's choice as well. Several of his college buddies died during the war. As for Lee's father, L.L. wasn't done "getting up and getting on" with things. Always ready to push on with new ventures, in 1943 he moved to South Boston (in business for himself, with a partner, Mr. Allred) to begin "Southside Wholesale Distributors." Eventually he wound up back in South Hill and once served as Mayor of the town, so things turned out all right for him as well, the self-made mountain man. Meanwhile, Lee took a job as a lawyer with the Department of Agriculture and wound up best friends with a fellow named Tom O'Reilly. By 1942, Tom and Lee had been sent out from Washington, D.C. to St. Louis, Missouri. Lee was 26 years old, happy with life and law. Then Tom and Lee started noticing the office mail girls: there was a tall, thin, striking-looking with auburn haired, and a short, perky blue-eyed blonde. The gentlemen promptly struck up a flirtation. In the weeks that followed, Tom developed an eye for the short, blue-eyed blonde, Jean, while Lee also developed an eye for the short, blue-eyed blonde. She looked just like Ruth Montgomery: pretty eyes, perky, rounded face. "Too late, Lee. Already got a date with her," said Tom one afternoon, "but I think I can set you up with her friend, Maxine." Maxine was the auburn-headed, tall one. She was shy and equally pretty and laughed at all of his jokes, so Lee got to thinking that might be all right after all.  L to R: Maxine's mother, Virginia Hay, Maxine's best friend in High School and Maxine - tall and thin, indeed (Pictured here her Senior year of High School) L to R: Maxine's mother, Virginia Hay, Maxine's best friend in High School and Maxine - tall and thin, indeed (Pictured here her Senior year of High School) Maxine Hay, for her part, liked Lee Bean from the start. Whenever she came through the offices, he'd put aside his paperwork to chat. She loved his laugh, his smile, his good looks, and the way he always had his shirt sleeves rolled up, the dark Welsh complexion a beautiful contrast to the crisp white starch of the sleeves. By the time he stood up and she saw he was on crutches, it was too late to matter. Some of life would be hard, yes, but what was the point of thinking like that when you could have those dark brown eyes to gaze into, and his laughter, and his heart. Really, what did anything matter when you were in love? Well, the matter turned out to be Maxine's mother. Virginia Hay was vehemently opposed to Lee. As they dated throughout Maxine's college years, Virginia continued to tell her what a poor choice she was making. "Only think what you're doing! Throwing your life away on a... on a LAWYER!" She couldn't admit Lee's handicap was a problem, so she blamed his doctorate of jurisprudence. If you'll just note the look on Virginia's face in the above photo, you won't be surprised to find she eventually demanded Maxine quit seeing him. The months that followed were miserable for the couple. The only thing they could both looked forward to was the marriage of her best friend, Jean, to Tom O'Reilly. She was to be Jean's maid of honor. Lee was to be Tom's best man. When the wedding day arrived, it had been twelve long months since Maxine and Lee had seen each other. After the ceremony, Lee approached Maxine, looked into her eyes and asked in his sweet southern drawl, "How you been, sugar?" After that, Virginia Hay was just going to have to find a way to get over it. Maxine and Lee were married in 1949 at Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg, Virginia. Their film footage of the moments before they left on their honeymoon. reveal Lee's parents looking on with pride... and a somewhat sour look on Virginia Hay's face. And there's Maxine, smiling like the sun just rose for the first time, and Lee, with a lovely grin, rushing to the getaway car so quickly his crutches all but disappear. Lee was a rarity: an honest lawyer who was remembered - and honored - for his integrity. And then there was the work that made him famous. During the Civil Rights movement, Virginia schools were in an uproar, and the racist faction in Arlington wanted to make certain desegregation never happened there. The U.S. Supreme Court had formed integration into law. Virginia had decided it did not have to integrate. It was time to stack the School Board in favor of racism - to make certain the Supreme Court would not get a toe-hold in Arlington County. A group of men, led by Mr. Robert Peck of the once well-known Peck Automobile in Arlington, asked Lee to serve on the Board. They took for granted that a boy raised in Florida and Southern Virginia would see things their way. That, and the fact that, as a lawyer, he'd be in danger of losing his law license in Virginia if he went against the Virginia Court's decision, seemed to seal the deal. There were two "liberals" on the board - one of which was Elizabeth Campbell who went on to found WETA Public Television. And there were two "conservatives." And than there was Lee. He'd come on the board promising to follow "a moderate course". So he went along with segregation... for a time. But he was a man of fairness, and, on Feb. 2, 1959, when it came time for the crucial vote on whether to integrate Arlington, Virginia Public Schools Lee voted with the liberals and Arlington became the first county in Virginia to desegregate public schools. The family soon received anonymous phone calls in the dead of night. Death threats. But Lee pressed on, standing firmly by what was right and fair. Then there was a second vote to be made. Now that they'd won for integration, they wanted to integrate as quickly as possible. Lee felt integration needed to be slowly invoked over time. He feared that the poor education the black children had had left them unprepared for public white schools. They would fail, he thought. He lost the vote, and the newspaper came down on him hard - as if he'd changed his mind on the issue. But he was right. A huge number did fail, but integration had begun (For details on Lee's involvement in Arlington County, Virginia desegregation visit Arlington County School, head to Arlington County Public Library's Oral History collection: Bean, L. Lee; Attorneys; School Board; Desegregation; L. Lee Bean Jr.’s Washington Post Obituary. And he remained a hero to integrationists. His youngest daughter can recall the strange excitement of finding herself in the car on a Sunday heading out into the far hills of Virginia where Lee would attend a small, black church and give the sermon. Throughout his life, he was called upon to speak. One evening he found himself at a lawyers' conference where he'd just been given a fine introduction. Lee approached the podium, looked down at the stand, and quickly looked back up. "I thank you so much, Jim, but I have to say... you've left me absolutely speechless. I mean to say, Jim, you've accidentally taken my notes, and I have no speech." As a lawyer, Lee's focus was Domestic Relations, and he became quite well known - famous, actually - for his work in the field, writing a book on Virginia Domestic Relations Law (University of Virginia, 1982) and for becoming President of both the Virginia Trial Lawyers and the Virginia Bar Association (only one other lawyer - Tom Moynihan of Winchester - has accomplished the same). And, yes, he was a skilled lawyer, he was best known for caring about his clients. His first question for a person intent on divorce was always have you tried counseling? In the 1980s, Maxine went to New York with a group of women to see the Kipps Bay Showhouse. The women knew each other only a first name basis. As they sat talking over lunch, the conversation veered to the realm of their respective nasty divorces. Harsh words for ex-husband, but even harsher words for the useless lawyers they'd had to represent them. But one lady kept saying she'd had a great experience - that her lawyer had done everything for her, and she was deeply grateful for his efforts. Who was that?, they all wanted to know. Lee Bean of Arlington, she replied. Maxine jumped in her seat a little, then leaned over to the woman next to her and whispered, "That's my husband!" He was a friend to all. The family once drove back to South Hill for a family reunion; Lee pulled up to the gas station and struck up a conversation with the attendant using a suddenly thick drawl - as though he'd only left town yesterday. It was clear he wanted to make an old friend comfortable talking to this fancy lawyer in a Lincoln Continental.  Maxine and Lee visiting UVA Maxine and Lee visiting UVA You'll notice most of these photos do not show Lee with crutches. Like F.D.R., Lee never liked to think of himself as handicapped and, when standing in place for any length of time, would put them aside. He appreciated handicap access - that was only fair - but otherwise, he let the subject drop. By middle age, Lee had become as powerfully built as L.L. In truth, the fact that Lee had to exercise everyday as he pulled his own weight around, throwing his hips forward to take every step, probably served to prolong his life. So, while other dads played "airplane" by laying on their back and flying the little ones on their knees, Lee just lay on the floor and flew his children by holding them high. So, he couldn't carry them up on his shoulders, but he could lay on the floor and let them come at him to try and tickle him, but he always won and then he'd tickle the life out them. But the children's favorite past-time was the dessert that came after dinner: listening to Lee's stories from his youth. And he never lost that sense of humor, so naturally, he was a member The Arlington Optimists Club (while at college, his youngest treasured the quick notes, tucked with a five dollar bill and a list of the Optimists Club Newsletter jokes - all his favorite jokes checked off), he and Maxine loved all forms of music, particularly swing, classical and Jazz (Maxine and Lee had gone to Eddie Condon's Club in New York City during their honeymoon), and in 1966, Maxine and Lee purchased a farm in Fauquier as a weekend retreat. Lee took to farm life like a duck to water. as did the family. "Bridle Tree Farm" in Sumerduck, Virginia, became the perfect spot to have horses, go fishing, swimming and renovate a beautiful of house the family could enjoy for decades. Lee always loved work as a trial lawyer (there's an actor in every Bean) and never wanted to miss a day of work, despite 50 years of walking with the help of Canadian Canes. Lee Bean away in 1989, a few months after the birth of his first grandson, Palmer Lee McMath. and in the end, he nearly got his wish. His third heart attack took him at age 73. He'd only missed half a day of work. "Lawyer L. Lee Bean, Jr. Dies - The Washington Post, Dec. 7, 1989 - https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1989/12/07/lawyer-l-lee-bean-jr-dies/efd366c3-128a-4883-b6a4-54fc62119453/

2 Comments

Meredith McMath

7/11/2023 03:18:57 pm

Thanks! You’re most welcome.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |